Warning Hashflags

Published 10 years, 8 months pastOver the weekend, I published “Time and Emotion” on The Pastry Box, in which I pondered the way we’re creating the data that the data-miners of the future will use to (literally) thoughtlessly construct emotional minefields — if we don’t work to turn away from that outcome.

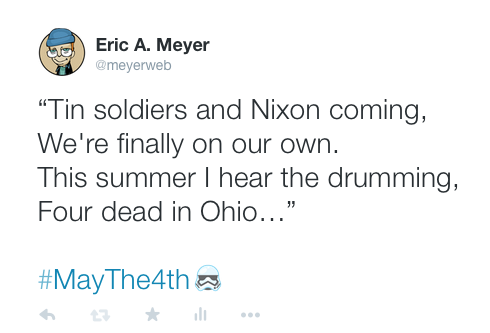

The way I introduced the topic was by noting the calendar coincidence of the Star Wars-themed tradition of “May the Fourth be with you” and the anniversary of the Kent State shootings in 1970, and how I observe the latter while most of the internet celebrates the former: by tweeting some song lyrics with a relevant hashtag, #maythe4th. I did as I said I would…and Twitter blindly added a layer of commentary with a very simple little content filter. On twitter.com and in the official Twitter app, a little Stormtrooper helmet was inserted after the hashtag #maythe4th.

So let’s review: I tweeted in remembrance of a group of National Guardsmen firing into a crowd of college students, wounding nine and killing four. After the date hashtag, there appeared a Stormtrooper icon. To someone who came into it cold, that could easily read as a particularly tasteless joke-slash-attack, equating the Guardsmen with a Nazi paramilitary group by way of Star Wars reference. While some might agree with that characterization, it was not my intent. The meaning of what I wrote was altered by an unthinking algorithm. It imposed on me a rhetorical position that I do not hold.

In a like vein, Thijs Reijgersberg pointed out that May 4th is Remembrance of the Dead Day in the Netherlands, an occasion to honor those who died in conflict since the outbreak of World War II. He did so on Twitter, using the same hashtag I had, and again got a Stormtrooper helmet inserted into his tweet. A Stormtrooper as part of a tweet about the Dutch remembrance of their war dead from World War II on. That’s…troublesome.

Michael Wiik, following on our observations, took it all one step further by tweeting a number of historical events collected from Wikipedia. I know several of my British chums would heartily agree with the 1979 tweet’s added layer of commentary, but there are others who might well feel enraged and disgusted. That could include someone who tweets about the election in celebration, the way people sometimes do about their heroes.

But what about appending a Stormtrooper helment to an observance of the liberation of the Neuengamme concentration camp in 1945? For that matter, suppose someone tweets May-4th birthday congratulations to a Holocaust survivor, or the child of a Holocaust survivor? The descendant of a Holocaust victim?

You might think that this is all a bit much, because all you have to do is avoid using the hashtag, or Twitter altogether. Those are solutions, but they’re not very useful solutions. They require humans to alter their behavior to accommodate code, rather than expecting code to accommodate humans; and furthermore, they require that humans have foreknowledge. I didn’t know the hashtag would get an emoji before I did it. And, because it only shows up in some methods of accessing Twitter, there’s every chance I wouldn’t have known it was there, had I not used twitter.com to post. Can you imagine if someone sent a tweet out, found themselves attacked for tweeting in poor taste, and couldn’t even see what was upsetting people?

And, as it happens, even #may4th wasn’t safe from being hashflagged, as Twitter calls it, though that was different: it got a yellow droid’s top dome (I assume BB-8) rather than a Stormtrooper helmet. The droid doesn’t have nearly the same historical baggage (yet), but it still risks making a user look like they’re being mocking or silly in a situation where the opposite was intended. If they tagged a remembrance of the 2007 destruction of Greensburg, Kansas with #may4th, for example.

For me, it was a deeply surreal way to make the one of the points I’d been talking about in my Pastry Box article. We’re designing processes that alter people’s intended meaning by altering content and thus adding unwanted context, code that throws pieces of data together without awareness of meaning and intent, code that will synthesize emotional environments effectively at random. Emergent patterns are happening entirely outside our control, and we’re not even thinking about the ways we thoughtlessly cede that control. We’re like toddlers throwing tinted drinking glasses on the floor to see the pretty sparkles, not thinking about how the resulting beauty might slice someone’s foot open.

We don’t need to stop writing code. We do need to start thinking.