As a member of the incredible team that’s worked so hard to create it, I couldn’t be more pleased to announce the publication of the findings of the 2007 Web Design Survey.

It’s amazing how many things this process broke. Right from the outset, the enormity of the entire enterprise pushed all sorts of things past their limits.

The first thing the survey broke was our expectations. I can only speak authoritatively for myself, but I think the general sense in the team was that we’d be really happy if the number of responses approached 10,000; I myself was expecting somewhere in the 7,000 – 8,000 range. Instead, we got 32,831 responses. So many people took the survey at once that it slowed down the Event Apart server, where the survey was hosted.

Although the survey software collected all that information with nary a hitch, getting it back out was another question. Over the first few days, I was grabbing snapshots of the results as they came in. That had to stop when an export request brought the entire server to a grinding halt. Turns out we’d hit a limitation in the software’s code that made exports of tables above a certain size run very, very slowly.

When everything was finished and it was time to run the final export, the same problem bit us again: only this time, we couldn’t get the data out at all. It was finally Mark Huot who extracted it by hacking the software a bit and running a custom-configured local server instance just to get it extracted in CSV format.

Which left us with a 35.8MB CSV file that needed to be cleaned a bit, as it had some funky characters in it that prevented a straight import into Excel (or anything else). Have you ever tried to load a 35.8MB text file into a text editor? It takes a while. At one point, I honestly feared I’d locked up BBEdit. And that was just to load it. Imagine doing find-and-replace operations. With grep. (Now imagine constructing the grep expressions needed without gacking half the file.)

But eventually we got the file scrubbed clean and imported into Excel. The end result was a 21.7MB Excel file. Have you ever tried to work with a 21.7MB file in Excel? It takes a while. Hell, just hitting “Save” sometimes meant a three-minute wait. And then there’s doing data analysis on a file that large. Have you ever…? Right, you get the idea.

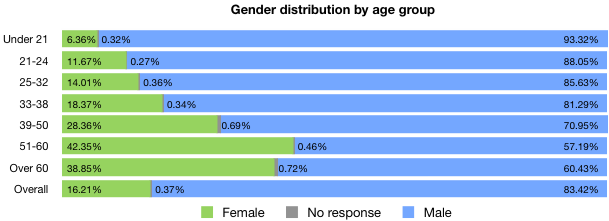

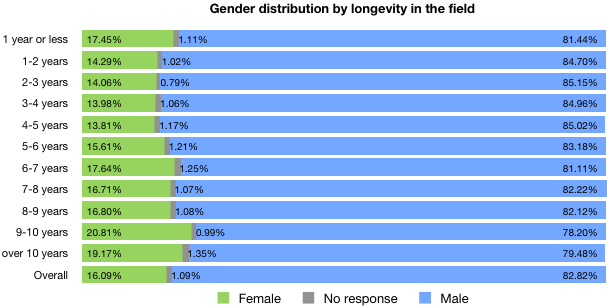

The next thing that broke was our ability to process the data in meaningful ways. I was able to pull some high-level numbers—what you might call surface analyses—for each of the questions. For example, I could tell you the breakdown of titles, or genders, or education levels; in effect, all the charts in the final report’s introduction (that is, Figures i – xxviii). At one point, I could even tell you what proportion of the respondents had 401(k)s. But when it came to looking more in-depth, I was out of my depth. Want to know the educational-level distribution of female part-time workers at non-profits? I was lost. A statistician I’m not.

So we hired two. Jeffrey and I decided to use some of the proceeds from An Event Apart to retain two professional statistical consultants, Alan Brickman and Larry Yu, and we worked with them to identify interesting questions and patterns. They did a superb job of not only breaking down the data for us, but also keeping our pattern-recognition impulses in check. It’s tempting to look at a spike in numbers and invent reasons for its existence, and they reined us in more than once.

For example, and here’s a tiny peek into the results, we found that the higher a respondent’s salary, the more likely they are to participate in formal training (Fig. 9.6, p. 73, in case you want to go straight there). But why? Do they make more because they undergo more training; or undergo more training because they can afford it, or can afford to make their company pay for it? Do not know, so cannot say.

Of course, it’s one thing to get a few hundred tables of numbers and a lengthy written summary from your consultants. It’s quite another to turn it into a report that distills it all down to the essence, and looks good to boot. And that’s where we started to heave real trouble.

I mean, sure, Excel can spit out charts like nobody’s business, but I have news: visually speaking, they really aren’t very good charts. I know you’re shocked to hear this. Perhaps under most circumstances that would be okay, but the charts that would go into our final report needed to look professional. And by that, I mean designery professional.

As Head Chart Guy, I grappled with Excel (the Office X version) for weeks. I learned more about Excel charting than I’d ever known, and still I could not get it to do what I wanted. Right aligning the left labels on a chart? The only way was to set the text rotation to something other than zero. Then they’d all right-align, but also not be straight horizontal labels. Plus they looked like crap that way, because there was no anti-aliasing happening on the text, or really anywhere else. And so on. We absolutely needed Excel to analyze the data, but its graphical output wasn’t what we needed.

So we looked around. We considered PlotKit; we thought about pure CSS graphs; we even considered hand-drawing every last chart in Illustrator. Eventually, we decided to give Numbers a try. And immediately broke it.

Remember the big ol’ data files I mentioned earlier? It turns out that Numbers was unable to even open them. We couldn’t do any of our analysis in Numbers. In hindsight, this was probably a good thing, because I don’t think it does anything like pivot tables, and those were absolutely fundamental to the whole process. One personal benefit of this whole process for me is that I finally learned how to create pivot tables in Excel. Strangely, it’s both easier and harder than you might expect.

So in the end, I produced needed data tables in Excel, copied them over to Numbers, and produced the charts there. In the process, I learned way more about Numbers than I ever really wanted to know. Jason and I could probably write a medium-sized book on all the things we learned, and learned to hate, about Numbers. (Like, legends aren’t directly attached to their charts. WTF?)

Which is not to say Numbers was a total disaster: far from it. All the charts you see in the report were created using Numbers, exported to PDF, and dropped into InDesign. There were a lot of things about Numbers that made the process a lot easier than it would have been, and that very definitely helped us stay organized. Of course, that just highlighted its limitations all the more harshly. (You can’t change the separation distance between labels and the chart area? WTF?)

And then there was the actual assembly, authoring, and proofreading. Finding typos that inverted claims, mismatches between numbers, charts that were incomprehensible, summary tables that were calculated along the wrong axis. All the innumerable errors that creep into a process, intensified and magnified by the unusually high information density of this particular project. Late-stage changes of approach, starting over in places, realizing that things were not as we thought they were. It’s the kind of thing that might lead one to break a web service.

And now it’s done. It’s out. We can rest.

It’s possible that you will not choose to rest, however. I’m very proud to say that we’re giving the data back to the community that gave it to us in the first place. Along with the report, we’re also providing anonymized copies of the complete survey data. Every single one of those 32,831 responses, available in three formats, with only the identifying information stripped away. If you want to fact-check our results, you can. If you want to dig deeper, go for it. If you want to investigate an area we passed over, please do. It’s all there. It’s all yours. It always was yours—we just collected it and held onto it for a little while, and for that trust and honor, we thank you.

So: go read it and let us know what you think. Tell us how we could do things better next year. Show us what we missed by producing your own analyses. And be ready for spring 2008, when we start the cycle anew.