CSS:TDG Update

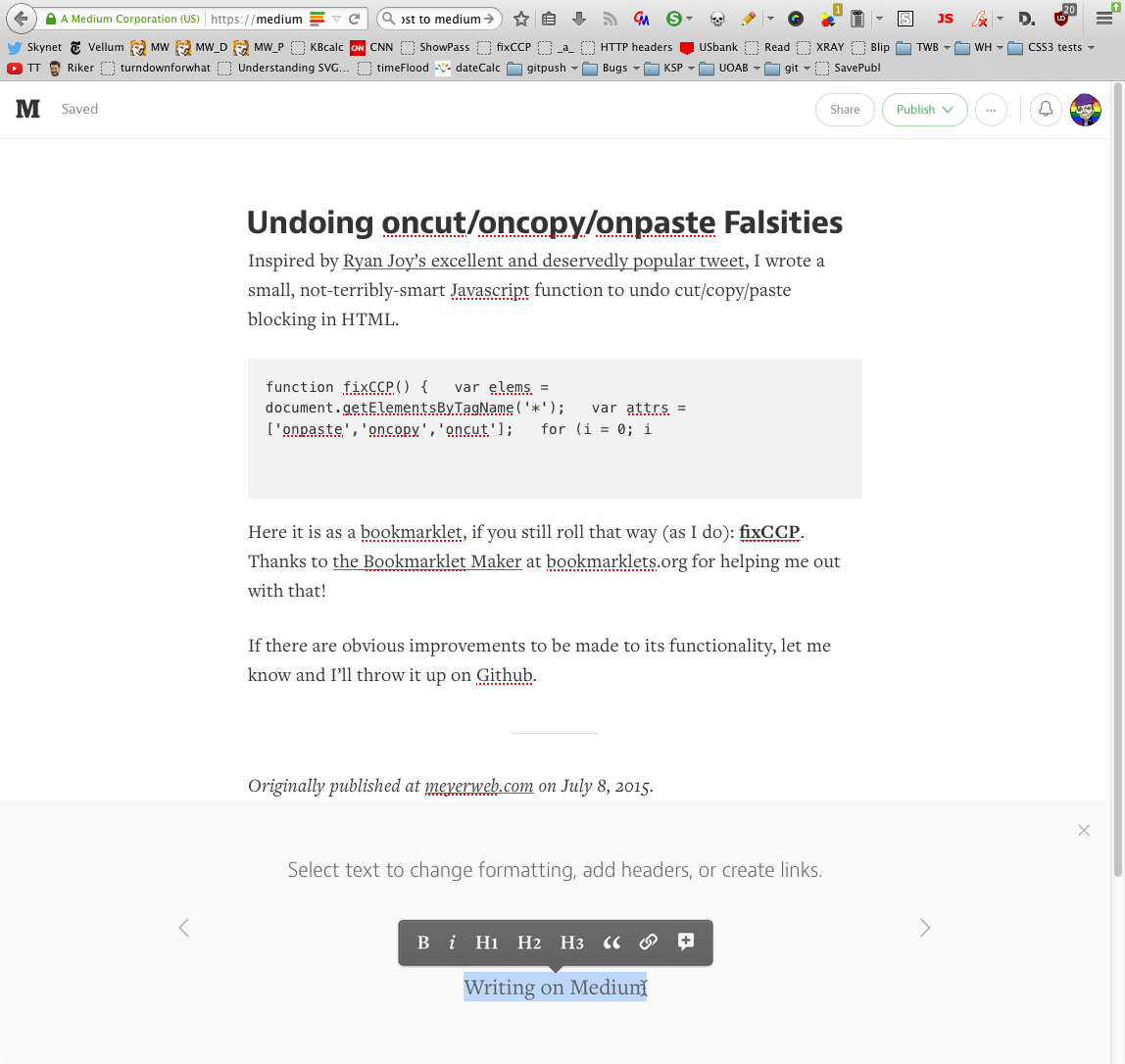

Published 10 years, 4 months pastIt’s time for a semi-periodic update on CSS: The Definitive Guide, 4th Edition! The basic news is that things are proceeding, albeit slowly. Eight chapters are even now available as ebooks or, in most cases, print-on-demand titles. Behold:

- CSS and Documents, which covers the raw basics of how CSS is associated with HTML, including some of the more obscure ways of strapping external styles to the document as well as media query syntax. It’s free to download in any of the various formats O’Reilly offers.

- Selectors, Specificity, and the Cascade, which combines two chapters to cover all of the various Level 3 selector patterns as well as the inner details of how specificity, inheritance, and cascade.

- Values, Units and Colors, which covers all the various ways you can label numbers as well as use strings. It also takes advantage of the new cheapness of color printing to use a bunch of nice color-value figures that aren’t forced to be all in grayscale.

- CSS Fonts, which dives into the gory details of

@font-faceand how it can deeply affect the use offont-related properties, both those we use widely as well as many that are quickly gaining browser support. - CSS Text, which covers all the text styles that aren’t concerned with setting the font face — stuff like indenting, decoration, drop shadows, white-space handling, and so on.

- Basic Visual Formatting in CSS, which covers how block, inline, inline-block, and other boxes are constructed, including the surprisingly-complicated topic of how lines of text are constructed. Very fundamental stuff, but of course fundamentals are called that for a reason.

- Transforms in CSS, which is currently FREE in ebook format, covers the

transformproperty and its closely related properties. 2D, 3D, it’s all here. - Colors, Backgrounds, and Gradients, which covers those three topics in FULL GLORIOUS COLOR, fittingly enough. Curious about the new background sizing options? Ever wondered exactly how linear and radial gradients are constructed? This book will tell you all that, and more.

Here’s what I have planned to write next:

- Padding, Borders, Outlines, and Margins — including the surprisingly tricky

border-image - Positioning – basically an update, with new and unexpected twists that have been revealed over the years (case in point)

- Grid Layout – though this is coming faster than many of us realize, I may put this one off for a little bit while we see how browser implementations go, and find out what changes happen as a result

My co-author, Estelle, has these three chapters/short books currently in process:

- Transitions

- Animations

- Flexbox

Beyond those 14 chapters, we have eight more on the roster, covering topics like floating, multicolumn layout, shapes, and more. CSS is big now, y’all.

So that’s where we are right now. Our hope is to have the whole thing written by the middle of 2016, at which point some interesting questions will have to be answered. While most of the book is fine in grayscale, there are some chapters (like Colors, Backgrounds, and Gradients) that really beenfit from being in color. Printing a 22-chapter book in color would make it punishingly expensive, even with today’s drastically lower cost of color printing. So what to do?

Not to mention, printing a 22-chapter book is its own level of difficulty. Even if we assume an average of 40 pages a chapter — an unreasonabnly low figure, but let’s go with it — that’s still a nine hundred page book, once you add front and back matter. The binding requirements alone gets us into the realm of punishingly expensive, even without color.

Of course, ebook readers don’t have to care about any of that, but some people (like me) really do prefer paper. So there will be some interesting discussions. Print in two volumes? Sell the individual chapter books in a giant boxed set, Chronicles of Narnia style? We’ll see!