Color Easing Isn’t Always Easy

Published 6 years, 2 months pastA fairly new addition to CSS is the ability to define midpoints between two color stops in a gradient. You can do this for both linear and radial gradients, but I’m going to stick with linear gradients in this piece, since they’re easier to show and visualize, at least for me.

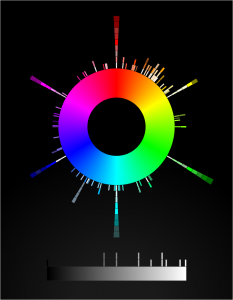

The way they work is that you can define a spot on the gradient where the color that’s a halfway blend between the two color stops is located. Take the mix of #00F (blue) with #FFF (white), for example. The color midway through that blend is #8080FF, a pale-ish blue. By default, that will land halfway between the two color stops. So given linear-gradient(90deg, blue 0px, white 200px), you get #8080FF at 100 pixels. If you use a more generic 90deg, blue, white 100%, then you get #8080FF at the 50% mark.

linear-gradient(90deg, blue, white 100%)

If you set a midpoint, though, the placement of #8080FF is set, and the rest of the gradient is altered to create a smooth progression. linear-gradient(blue 0px, 150px, white 200px) places the midway color #8080FF at 150 pixels. From 0 to 150 pixels is a gradient from #F00 to #8080FF, and from 150 pixels to 200 pixels is a gradient from #8080FF to #FFF. In the following case, #8080FF is placed at the 80% mark; if the gradient is 200 pixels wide, that’s at 160 pixels. For a 40-em gradient, that midpoint color is placed at 32em.

linear-gradient(90deg, blue, 80%, white 100%)

You might think that’s essentially two linear gradients next to each other, and that’s an understandable assumption. For one, that’s what used to be the case. For another, without setting midpoints, you do get linear transitions. Take a look at the following example. If you hover over the second gradient, it’ll switch direction from 270deg to 90deg. Visually, there’s no difference, other than the label change.

linear-gradient(<angle>, blue, white, blue)

That works out because the easing from color stop to color stop is, in this case, linear. That’s the case here because the easing midpoints are halfway between the color stops — if you leave them out, then they default to 50%. In other words, linear-gradient(0deg, blue, white, blue) and linear-gradient(0deg, blue, 50%, white, 50%, blue) have the same effect. This is because the midpoint easing algorithm is based on logarithms, and is designed to yield linear easing for a 50% midpoint.

Still, in the general case, it’s a logarithm algorithm (which I love to say out loud). If the midpoint is anywhere other than exactly halfway between color stops, there will be non-linear easing. More to the point, there will be non-linear, asymmetrical easing. Hover over the second gradient in the following example, where there are midpoints set at 10% and 90%, to switch it from 270deg to 90deg, and you’ll see that it’s only a match when the direction is the same.

linear-gradient(<angle>, blue, 10%, white, 90%, blue)

This logarithmic easing is used because that’s what Photoshop does. (Not Mosaic, for once!) Adobe proposed adding non-linear midpoint easing to gradients, and they had an equation on hand that gave linear results in the default case. It was also what developers would likely need to match if they got handed a Photoshop file with eased gradients in it. So the Working Group, rather sensibly, went with it.

The downside is that under this easing regime, it’s really hard to create symmetric non-linear line gradients. It might even be mathematically impossible, though I’m no mathematician. Regardless, its very nature means you can’t get perfect symmetry. This stands in contrast to cubic Bézier easing, where it’s easy to make symmetric easings as long as you know which values to swap. And there are already defined keywords that are symmetric to each other, like ease-in and ease-out.

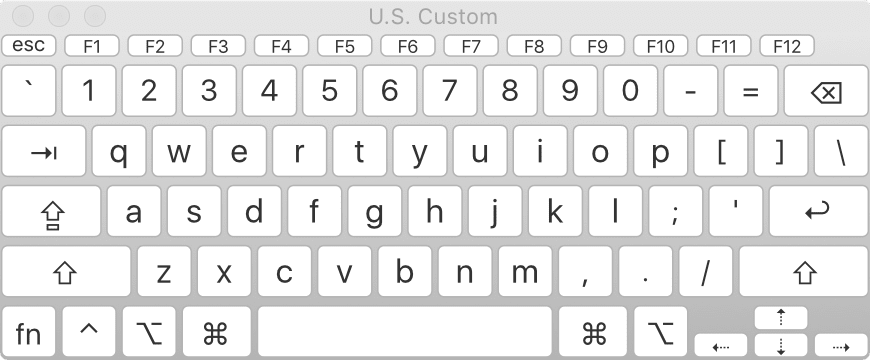

If you’re up for the work it takes, it’s possible to get some close visual matches to cubic Bézier easing using the logarithmic easing we have now. With a massive assist from Tab Atkins, who wrote the JavaScript I put to use, I created a couple of CodePens to demonstrate this. In the first, you can see that linear-gradient(90deg, blue, 66.6%, white) is pretty close to linear-gradient(90deg, blue, ease-in, white). There’s a divergence around the 20-30% area, but it’s fairly minor. Setting an interim color stop would probably bring it more in line. That’s partly how I got a close match to linear-gradient(90deg, blue, ease-out, white), which came out to be linear-gradient(90deg, blue, 23%, #AFAFFF 50%, 68%, white 93%).

Those examples are all one-way, however — not symmetrical. So I set up a second CodePen where I explored recreations of a few symmetrical non-linear gradients. The simplest example matches linear-gradient(90deg, blue, ease-in, white, ease-out, blue) with linear-gradient(90deg, blue, 33.3%, white 50%, 61.5%, #5050FF 75%, 84%, blue 93%), and they only get more complex from there.

I should note that I make no claim I’ve found the best possible matches in my experiments. There are probably more accurate reproductions possible, and there are probably algorithms to work out what they would be. Instead, I did what most authors would do, were they motivated to do this at all: I set some stops and manually tweaked midpoints until I got a close match. My basic goal was to minimize the number of stops and midpoints, because doing so meant less work for me.

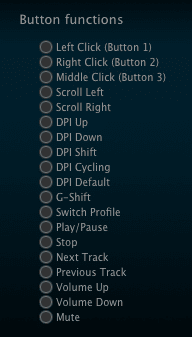

So, okay, we can recreate cubic Bézier easing with logarithmic midpoints. Still, wouldn’t it be cool to just allow color easing using cubic Béziers? That’s what Issue #1332 in the CSS Working Group’s Editor Drafts repository requests. From the initial request, the idea has been debated and refined so that most of the participants seem happy with a syntax like linear-gradient(red, ease-in-out, blue).

The thing is, it’s generally not enough to have an accepted syntax — the Working Group, and more specifically browser implementors, want to see use cases. When resources are finite, requests get prioritized. Solving actual problems that authors face always wins over doing an arguably cool thing nobody really needs. Which is this? I don’t know, and neither does the Working Group.

So: if you have use cases where cubic Bézier easing for gradient color stops would make your life easier, whether it’s for drop shadows or image overlays or something I could never think of because I haven’t faced it, please add them to the GitHub issue!