Half Life

Published 8 years, 8 months past

Three years ago, Rebecca took her last breaths.

She’s been gone for half her life. Half the time she had with us, elapsed in absence.

It’s still hard to comprehend. The old adage that you don’t get over it, but you get used to it, holds true. I’m used to her absence. I still think of her daily, usually multiple times a day, reminded one way or another. The reminders can spring from moments of joy that I suddenly realize she isn’t there to share, or from moments of profound sorrow over the state of everything, or just from spotting an unexpected flash of purple.

In the initial grieving, each moment of remembrance was like an enormous jagged spike driven violently through my chest, impaling me in an anguish I could not actually feel, even as I experienced it. My breath would hitch to a stop as I remembered the hitch in hers, as her body finally relaxed and the space between each breath got longer and longer, even as each breath was a fractional bit fainter than the one before.

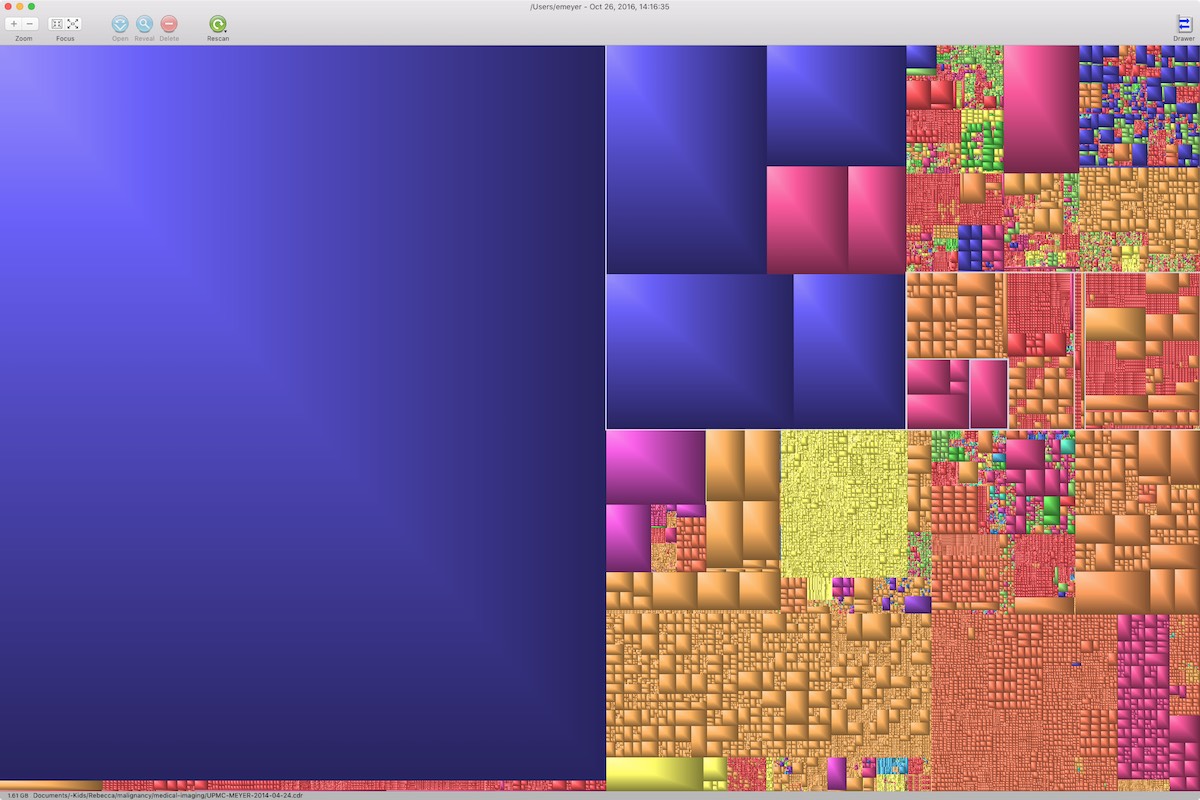

My grief has similarly faded, these last three years. That terrible, transfixing pain has its own slope of decay, if you let it decay, dropping into a long tail of quiescence. If you’ve ever suffered a major injury, then you know what I mean. The initial pain is overwhelming, filling your entire awareness and leaving room for nothing else. That fades into a massive suffering as the injury is addressed. After the initial recovery, you come to live with a constant pain that is manageable, if utterly draining to endure. After a longer while, that becomes an ongoing ache, easily aggravated but also somewhat possible to ignore for short periods. And so on and so on, until months or years later, it’s a twinge you get every now and then, maybe a dull ache when the weather changes or you shift your weight the wrong way. Something you can live with, but also something you can never fully forget.

I can still sometimes feel the spikes that were driven into me, but distantly, around the edges where the scar tissue grew to fill the latticework of grief. As you might feel the shadows of the pins that put your leg back together, or the echo of the holes drilled into your skull to seat the halo brace.

We went to visit her grave this afternoon. It was our first time back since last year’s memorial visit. I’d thought of going from time to time in the intervening year, and resisted. I’m not entirely certain why, but it felt like the right decision. Not the decision I wanted to make, but the right one.

We were astonished to find that the artificial flowers and rainbow spinner placed there last year were still in place, faded and worn. The groundskeepers had carefully mowed around them. Perhaps that’s why the small Rainbow Dash toy was still there, still nestled against the top edge of the marker. It, too, was faded from the year of sun and rain and ice, but still had the same jaunty pose and smiling face.

It reminded me of Rebecca, and I smiled a little.

I noticed dirt had settled into some of the letters, and resolved to return another day to clean them out. Maybe polish the granite face a bit, to see if I could restore some of its initial luster. Nothing I could do would preserve that forever; the slow decay of time and weather never pauses, not even in deference to the memory of a little girl who lived too short a life, no matter how fully she lived it.

In the long run, the marker will be worn smooth, settling through a long period of becoming harder and harder to read until eventually, it fades completely from understanding. That can’t be avoided, but it can be postponed a little bit. As long as I’m here and able, I can put in a little periodic effort to undo some of the damage done. Put things partly right. It might seem futile, but sometimes small acts in the face of futility is the best you can do.

You don’t get over it. But you get used to it.