In the middle of last month (July 2018), I found myself staring at a projector screen, waiting once again to see if Wikipedia would load. If I was lucky, the page started rendering 15-20 seconds after I sent the request. If not, it could be closer to 60 seconds, assuming the browser didn’t just time out on the connection. I saw a lot of “the server stopped responding” over the course of a few days.

It wasn’t just Wikipedia, either. CNN International had similar load times. So did Google’s main search page. Even this here site, with minimal assets to load, took a minimum of 10 seconds to start rendering. Usually longer.

In 2018? Yes. In rural Uganda, where I was improvising an introduction to web development for a class of vocational students, that’s the reality. They can have a computer lab full of Dell desktops running Windows or rows of Raspberry Pis running Ubuntu or whatever setup there is, but when satellites in geosynchronous earth orbit are your only source of internet, you wait. And wait. And wait.

I want to explain why — and far more importantly, how we’ve made that experience interminably worse and more expensive in the name of our comfort and security.

First, please consider the enormously constrained nature of satellite internet access. If you’re already familiar with this world, skip ahead a few paragraphs; but if not, permit me a brief description of the challenges.

For geosynchronous-satellite internet access, the speed of light become a factor in ping times: just having the signals propagate through a mixture of vacuum and atmosphere chews up approximately half a second of travel time over roughly 89,000 miles (~152,000km). If that all that distance were vacuum, your absolute floor for ping latency is about 506 milliseconds.

That’s just the time for the signals to make two round trips to geosynchronous orbit and back. In reality, there are the times to route the packets on either end, and the re-transmission time at the satellite itself.

But that’s not the real connection killer in most cases: packet loss is. After all, these packets are going to orbit and back. Lots of things along those long and lonely signal paths can cause the packets to get dropped. 50% packet loss is not uncommon; 80% is not unexpected.

So, you’re losing half your packets (or more), and the packets that aren’t lost have latency times around two-thirds of a second (or more). Each.

That’s reason enough to set up a local caching server. Another, even more pressing reason is that pretty much all commercial satellite connections come with data caps. Where I was, their cap was 50GB/month. Beyond that, they could either pay overages, or just not have data until the next month. So if you can locally cache URLs so that they only count against your data usage the first time they’re loaded, you do that. And someone had, for the school where I was teaching.

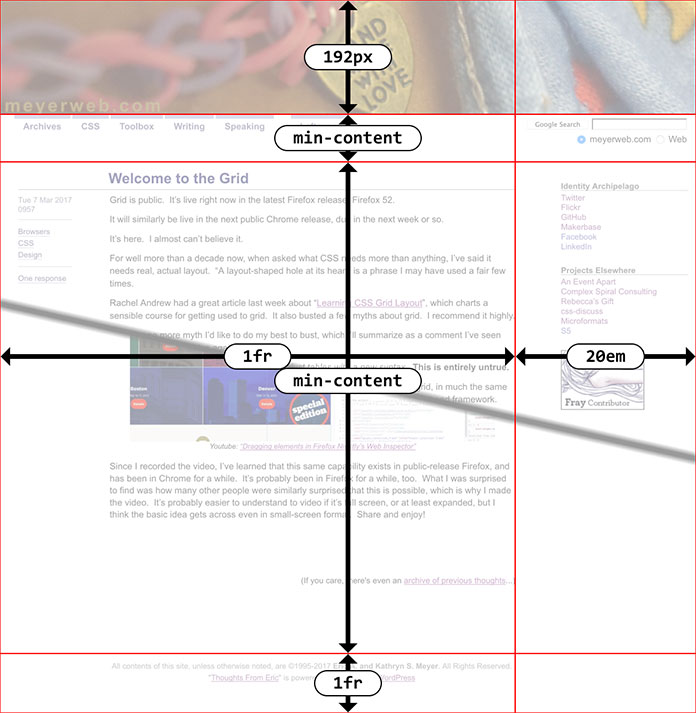

But there I stood anyway, hoping my requests to load simple web pages would bear fruit, and I could continue teaching basic web principles to a group of vocational students. Because Wikipedia wouldn’t cache. Google wouldn’t cache. Meyerweb wouldn’t cache. Almost nothing would cache.

Why?

HTTPS.

A local caching server, meant to speed up commonly-requested sites and reduce bandwidth usage, is a “man in the middle”. HTTPS, which by design prevents man-in-the-middle attacks, utterly breaks local caching servers. So I kept waiting and waiting for remote resources, eating into that month’s data cap with every request.

The drive to force every site on the web to HTTPS has pushed the web further away from the next billion users — not to mention a whole lot of the previous half-billion. I saw a piece that claimed, “Investing in HTTPS makes it faster, cheaper, and easier for everyone.” If you define “everyone” as people with gigabit fiber access, sure. Maybe it’s even true for most of those whose last mile is copper. But for people beyond the reach of glass and wire, every word of that claim was wrong.

If this is a surprise to you, you’re by no means alone. I hadn’t heard anything about it, so I asked a number of colleagues if they knew about the problem. Not only had they not, they all reacted the same way I did: this must not be an actual problem, or we’d have heard about it! But no.

Can we do anything? For users of up-to-date browsers, yes: service workers create a “good” man in the middle that sidesteps the HTTPS problem, so far as I understand. So if you’re serving content over HTTPS, creating a service worker should be one of your top priorities right now, even if it’s just to do straightforward local caching and nothing fancier. I haven’t gotten one up for meyerweb yet, but I will do so very soon.

That’s great for modern browsers, but not everyone has the option to be modern. Sometimes they’re constrained by old operating systems to run older browsers, ones with no service-worker support: a lab full of Windows XP machines limited to IE8, for example. Or on even older machines, running Windows 95 or other operating systems of that era. Those are most likely to be the very people who are in situations where they’re limited to satellite internet or other similarly slow services with unforgiving data caps. Even in the highly-wired world, you can still find older installs of operating systems and browsers: public libraries, to pick but one example. Securing the web literally made it less accessible to many, many people around the world.

Beyond deploying service workers and hoping those struggling to bridge the digital divide make it across, I don’t really have a solution here. I think HTTPS is probably a net positive overall, and I don’t know what we could have done better. All I know is that I saw, first-hand, the negative externality that was pushed onto people far, far away from our data centers and our thoughts.

My thanks to Tim Kadlec and Ethan Marcotte for their feedback and insight while I was drafting this post, and to Lara Hogan and Aaron Gustafson for their early assistance wth my research.