In the face of tragedy and grief, it’s hard to know what to say or do. And one thing I’ve noticed is that some people — not most, maybe even not many, but more than enough — say and do what they think would help them, without really considering what might be helpful to the person who’s grieving.

I don’t really want to get into the doing side of things at this point, but I can definitely talk about the saying. The most basic rule is: don’t let your discomfort with tragedy and grief push you into saying whatever comes to mind. A person’s grief is not a wall against which you should throw a spaghetti pot of nostrums, hoping that one of them will help. Maybe one will, but the harm likely caused by the others will outweigh it.

The second most basic rule is: don’t assume that a grieving person believes what you believe, or even that they believe what they believed before the tragedy. They may surprise or even shock you. The atheist may suddenly talk about an afterlife; the theist may angrily reject the existence of higher powers. These may be temporary shifts, or not, but they are raw, honest expressions of grief. Apply this rule in the exercise of the most basic rule, above.

Right now, I can only address this from the perspective of a grieving parent, so I will, though this all does apply to anyone who’s grieving — the child of a dead parent, the close friend of the recently deceased, and so on. Let’s start out with things you should say to a grieving parent.

“I’m so sorry.”

You’ve let them know you feel sorrow for them, are thinking about them, and are generally there in support of them. It seems like a lot for so little a sentence, but it’s all there. I think this is just about the most universally acceptable thing you can say to a grieving parent, and it also has the benefit of being the most appropriate thing to say.

Be prepared for them to say “me too” or something like that; otherwise, they’ll probably thank you. Do not tell them that no thanks are necessary. Let them acknowledge your care and support in what is likely the only way they can manage, with the only words they can find. Which leads us to the next thing you can fairly safely say.

“There are no words.”

Because after expressing your sorrow, there really aren’t. There are no words that can explain it, no words that can make it better, no words that can take away their anguish. I doubt there ever will be.

Beyond those two things, you can offer to help in some way — which is part of the doing that I said I wasn’t going to get into, but I’ll say here that you should only say this if you’re willing to do laundry or dishes or whatever else they request — or just sit quietly with them until they speak. Then follow their lead in the conversation. They may not speak at all, even if you sit with them for hours. Be okay with this, or be somewhere else.

All right, so what do you not say to a grieving parent? Honestly, we could be here all day with that, but I’ll skip over the ones that are obviously Just Wrong and address some of the most common ones that seem to pass by without comment. And yes, I’ve had all of them said, tweeted, or Facebooked at me, or at least very near me.

Of course, all of these are dependent on the parent in question. If they say their child is in a better place now, you can absolutely agree with them. In fact, you should agree with them, or at least refrain from disagreement, regardless of whatever you personally believe.

Because that’s what you do if a grieving parent expresses a belief you don’t hold: You agree with them. Now is not the time to be undermining whatever framework is holding them together; they have little enough of that as it is. If you’re religious and a non-religious parent says that their loved one is gone forever, not existing at all, you go along with it. If you’re non-religious and a grieving religious parent says their loved one is in a better place, in the arms of God, you go along with it. This is about them, not you. Adhere to the Ring Theory at all times.

That said, here we go.

“How are you doing?”

How do you think the parent of a dead child is doing? Okay, I admit that this might be acceptable if you know them very well or if enough time has passed — though how could you know if enough time has passed? — and because it comes from a place of concern for their well-being, this might get half a pass. Except what it usually does is force them to either lie conventionally (“I’m okay”) or tell the painful, probably swear-heavy truth. Better would be “I’ve been thinking about you” or even “I’ve been worried about how you’re doing”, though not by very much.

It’s also very much the case that this has been culturally ingrained for many of us; it’s just a longer way of saying “hello”, fired off without thinking, and so it just slips out. Grief creates an extraordinary circumstance, though, and you need to go into it challenging all of your preconceived notions about how to interact with other people. Be aware of what you’re about to say and how it might affect the person in front of you. (I mean, you should probably always do that anyway, but make sure you do it in this situation.)

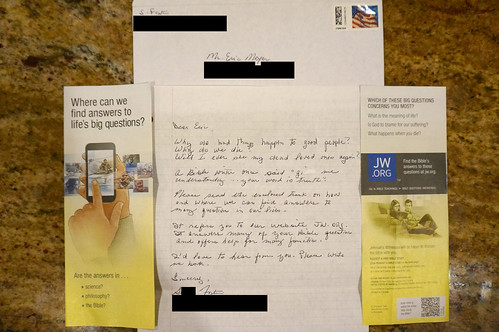

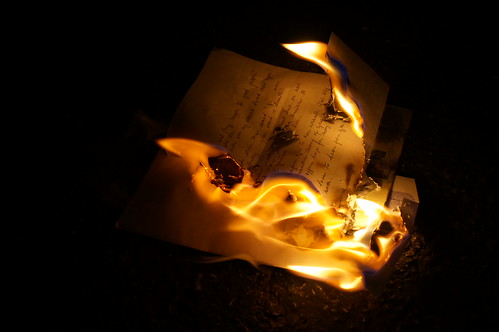

“It’s all part of God’s plan.” / “God has a special plan for them.” / “Everything is in God’s hands.”

You just told the parent of a dead child that God planned the death of their child. That God meant for it to happen, wanted it to happen, and in fact arranged events so that it would be sure to happen. This is not comforting. It is very much like the opposite.

“God needed another angel in Heaven.”

You just told the parent of a dead child that their loved one is gone because an all-powerful deity took their child away from them, on purpose, for its needs, not caring what it did to them. Also, if they don’t believe in God (or even a version of God sufficiently similar to yours), you just said the equivalent of “Santa needed another elf in his workshop.” Would you say that to a dead child’s parent? Then don’t say this either.

“Now they’re watching over you.”

You just reminded the parents of a dead child that for all their care and efforts, they could not protect their loved one from untimely death, which is pretty much the most basic responsibility a parent feels. Furthermore, it is the job (some would say calling, others would say privilege) of parents to watch over and protect their children, not the other way around. Telling them that this arrangement has now been inverted does not help.

“They’re in a better place now.” / “They’re where they belong.”

You just told the parent of a dead child that there is a place better for them than the home that sheltered them and the family that cherished them. That the child truly belongs somewhere other than with the people who loved them most. Don’t do that.

“Everything happens for a reason.”

You just implied that the child is dead because something their parents did resulted in the death. That wasn’t the intent, but it’s still in there, easily picked up on by parents racked with overwhelming regret and, very possibly, guilt. (Even parents who did everything they could in a no-win situation are likely to feel guilt that they didn’t do more or couldn’t find a way out.)

“Maybe it’s for the best.”

You just told the parent of a dead child that it’s better their child is dead than still alive. No. Just no.

The one I almost included was “I’m praying for you”, because you don’t always know what the other person thinks of prayer. In general, though, I think most non-religious people (even grieving parents) will mentally translate it to “I’m thinking of you and care about you”. Of course, if you know for a fact the grieving parent is non-religious, you should probably think hard about skipping this one. You can still pray for the non-religious, obviously, but say that you’ve been thinking about them.

There are a bunch more that are borderline. “At least they aren’t suffering any more” is very risky, for example, even if the child was in fact suffering greatly before they died. It reminds the parent of their child’s suffering, for example, and they may feel guilt as well as grief about that (see above).

As a last note, be careful about what terminology you use regarding death. Some parents won’t want to say or hear that word, preferring instead phrases like “passed away” or “passed on”. Others actually find phrases like “passed away” or “lost” to be more painful. Again, take your cues from the griever. If possible, don’t use any death-related terminology until they do, and then use the words they do.

To sum up: think hard about what will help them rather than what will soothe you; do not contradict expressions of grief even when they conflict with your beliefs; be sure to adhere to the Ring Theory; take your cues from the griever. And be prepared for just about anything.

My thanks to Gini Judd, Kate Kikel, and TJ Luoma for their pre-publication feedback on this post.