Custom Asidenotes

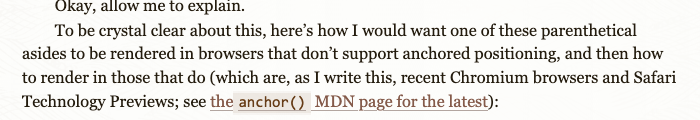

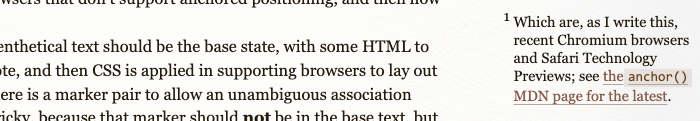

Published 4 months, 1 week pastPreviously on meyerweb, I crawled through a way to turn parenthetical comments into sidenotes, which I called “asidenotes”. As a recap, these are inline asides in parentheses, which is something I like to do. The constraints are that the text has to start inline, with its enclosing parentheses as part of the static content, so that the parentheses are present if CSS isn’t applied, but should lose those parentheses when turned into asidenotes, while also adding a sentence-terminating period when needed.

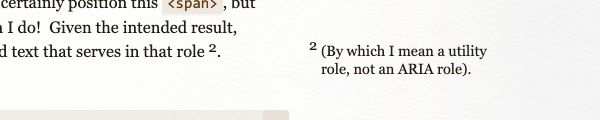

At the end of that post, I said I wouldn’t use the technique I developed, because the markup was too cluttered and unwieldy, and there were failure states that CSS alone couldn’t handle. So what can we do instead? Extend HTML to do things automatically!

If you’ve read my old post “Blinded By the DOM Light”, you can probably guess how this will go. Basically, we can write a little bit of JavaScript to take an invented element and Do Things To It™. What things? Anything JavaScript makes possible.

So first, we need an element, one with a hyphen in the middle of its name

<aside-note>(actual text content)</aside-note>Okay, great! Thanks to HTML’s permissive handling of unrecognized elements, this completely new element will be essentially treated like a <span> in older browsers. In newer browsers, we can massage it.

class asideNote extends HTMLElement {

connectedCallback() {

let marker = document.createElement('sup');

marker.classList.add('asidenote-marker');

this.after(marker);

}

}

customElements.define("aside-note",asideNote);With this in place, whenever a supporting browser encounters an <aside-note> element, it will run the JS above. Right now, what that does is insert a <sup> element just after the <aside-note>.

“Whoa, wait a minute”, I thought to myself at this point. “There will be browsers (mostly older browser versions) that understand custom elements, but don’t support anchor positioning. I should only run this JS if the browser can position with anchors, because I don’t want to needlessly clutter the DOM. I need an @supports query, except in JS!” And wouldn’t you know it, such things do exist.

class asideNote extends HTMLElement {

connectedCallback() {

if (CSS.supports('bottom','anchor(top)')) {

let marker = document.createElement('sup');

marker.classList.add('asidenote-marker');

this.after(marker);

}

}

}That will yield the following DOM structure:

<aside-note>(and brower versions)</aside-note><sup></sup>

That’s all we need to generate some markers and do some positioning, as was done in my previous post. To wit:

@supports (anchor-name: --main) {

#thoughts {

anchor-name: --main;

}

#thoughts article {

counter-reset: asidenotes;

}

#thoughts article sup {

font-size: 89%;

line-height: 0.5;

color: inherit;

text-decoration: none;

}

#thoughts article aside-note::after,

#thoughts article aside-note + sup::before {

content: counter(asidenotes);

}

#thoughts article aside-note {

counter-increment: asidenotes;

position: absolute;

anchor-name: --asidenote;

top: max(anchor(top), calc(anchor(--asidenote bottom, 0px) + 0.67em));

bottom: auto;

left: calc(anchor(--main right) + 4em);

max-width: 23em;

margin-block: 0.15em 0;

text-wrap: balance;

text-indent: 0;

font-size: 89%;

line-height: 1.25;

list-style: none;

}

#thoughts article aside-note::before {

content: counter(asidenotes);

position: absolute;

top: -0.4em;

right: calc(100% + 0.25em);

}

#thoughts article aside-note::first-letter {

text-transform: uppercase;

}

}I went through a lot of that CSS in the previous post, so jump over there to get details on what all that means if the above has you agog. I did add a few bits of text styling like an explicit line height and slight size reduction, and changed all the asidenote classes there to aside-note elements here, but nothing is different with the positioning and such.

Let’s go back to the JavaScript, where we can strip off the leading and trailing parentheses with relative ease.

class asideNote extends HTMLElement {

connectedCallback() {

if (CSS.supports('bottom','anchor(top)')) {

let marker = document.createElement('sup');

marker.classList.add('asidenote-marker');

this.after(marker);

let inner = this.innerText;

if (inner.slice(0,1) == '(' && inner.slice(-1) == ')') {

inner = inner.slice(1,inner.length-1);}

this.innerText = inner;

}

}

}This code looks at the innerText of the asidenote, checks to see if it both begins and ends with parentheses <aside-note>’s innerText to be that stripped string. I decided to set it up so that the stripping only happens if there are balanced parentheses because if there aren’t, I’ll see that in the post preview and fix it before publishing.

I still haven’t added the full stop at the end of the asidenotes, nor have I accounted for asidenotes that end in punctuation, so let’s add in a little bit more code to check for and do that:

class asideNote extends HTMLElement {

connectedCallback() {

if (CSS.supports('bottom','anchor(top)')) {

let marker = document.createElement('sup');

marker.classList.add('asidenote-marker');

this.after(marker);

let inner = this.innerText;

if (inner.slice(0,1) == '(' && inner.slice(-1) == ')') {

inner = inner.slice(1,inner.length-1);}

if (!isLastCharSpecial(inner)) {

inner += '.';}

this.innerText = inner;

}

}

}

function isLastCharSpecial(str) {

const punctuationRegex = /[!/?/‽/.\\]/;

return punctuationRegex.test(str.slice(-1));

}

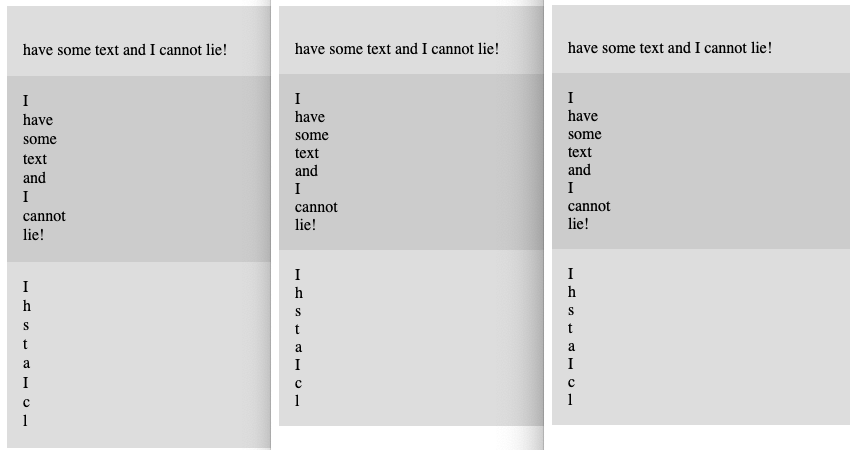

And with that, there is really only one more point of concern: what will happen to my asidenotes in mobile contexts? Probably be positioned just offscreen, creating a horizontal scrollbar or just cutting off the content completely. Thus, I don’t just need a supports query in my JS. I also need a media query. It’s a good thing those also exist!

class asideNote extends HTMLElement {

connectedCallback() {

if (CSS.supports('bottom','anchor(top)') &&

window.matchMedia('(width >= 65em)').matches) {

let marker = document.createElement('sup');

marker.classList.add('asidenote-marker');

this.after(marker);

Adding that window.matchMedia to the if statement’s test means all the DOM and content massaging will be done only if the browser understands anchor positioning and the window width is above 65 ems, which is my site’s first mobile media breakpoint that would cause real layout problems. Otherwise, it will leave the asidenote content embedded and fully parenthetical. Your breakpoint will very likely differ, but the principle still holds.

The one thing about this JS is that the media query only happens when the custom element is set up, same as the support query. There are ways to watch for changes to the media environment due to things like window resizes, but I’m not going to use them here. I probably should, but I’m still not going to.

So: will I use this version of asidenotes on meyerweb? I might, Rabbit, I might. I mean, I’m already using them in this post, so it seems like I should just add the JS to my blog templates and the CSS to my stylesheets so I can keep doing this sort of thing going forward. Any objections? Let’s hear ’em!