Fixed Monospace Sizing

Published 16 years, 1 week pastMonospace text sizing is, from time to time, completely unintuitive and can be quite maddening if you don’t look at it in exactly the right way. Fortunately, there is a pretty simple workaround, and it’s one you might want to consider using even if you weren’t aware that a problem existed.

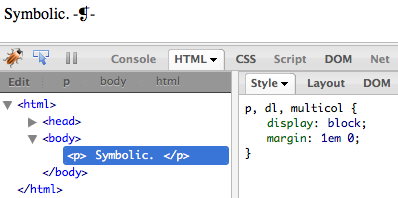

But first, allow me to lay some foundations. Assuming no other author styles beyond the ones shown, consider the following:

span {font-family: monospace;}

<p>This is a 'p' with a <span>'span'</span> inside.</p>

All right, what should be the computed font-size of the span element? Remember, there are no other author styles being applied.

The savvier among you will have said: “It depends, but most likely 13px.” That’s because here, the size of the monospace text is controlled by the browser’s preferences. The vast majority of users, of course, have never touched their default settings of “16” for proportional fonts and “13” for monospace/fixed fonts. For them, then, the answer is 13px. Similarly, if I’d asked about the p element’s computed font-size, the answer would be: “It depends, but most likely 16px.”

So let’s add a bit more and see where we land.

span {font-family: monospace; font-size: 1em;}

<p>This is a 'p' with a <span>'span'</span> inside.</p>

As before: bearing in mind that there are no other author styles, what should be the computed font-size of the span element?

In this case, building on the previous question and answer, you might say, “It depends, but most likely 16px.” The reasoning here is pretty straightforward: since the computed font-size of the p element is 16px, the font-size: 1em; assigned to the span will result in it having the same size.

And that’s true… in two of five browsers I tested: Opera 10 and Internet Explorer 8. In the other three I tested—Firefox 3.6, Safari 4, and Chrome 4—the computed (and rendered) font-size of the span is 13px, the same as in our first example. This result holds true if the rule is changed to use font: 1em monospace; instead of the two separate properties. The behavior continues to persist even when adding specific font families, like Courier New, Courier, Andale Mono, and so on to the rule. It also persists if 1em is converted to 100%.

So in other words, even though I have written CSS that explicitly says “Make the font-size of this element the same as its parent”, three of five browsers apparently ignore me.

I say “apparently” because what’s happening is that those browsers are allowing the span to inherit the default font-size from its parent (and thus, indirectly, all its ancestors), but the default font-size is medium. If you go look up medium, you find out that it doesn’t have a defined numeric size. So what those browsers do is equate medium with the preference settings, which means it’s different for monospace fonts than for everything else.

In other words, those three browsers are doing something like this:

- This

spanneeds to have the samefont-sizeas its parent element. - The parent’s

font-sizeismedium, even though when my web inspector (or an author’s DOM script) asks, I report the16pxI used to output the text. So thespan‘sfont-sizeis actuallymedium. - This

medium-sizedspanis using a monospace font. The preference setting for monospace is “13”, and I equatemediumwith the preference setting, so I’ll output thespanusing 13-pixel text.

Opera 10, as I said, doesn’t do this, even if your monospace font preference setting is the default value of “13” or indeed different from the preference for non-monospace fonts. And IE8 doesn’t appear to do it either, although you can’t set numeric font size preferences in IE8 so what it’s actually doing is open to interpretation. Oh, IE8, you inscrutable little scamp, you.

All that might seem reasonable enough, but it turns out that’s not the whole story. No, the three resizing browsers are being a good deal more “clever”, if that’s actually the word I want, than that. In fact, what those browsers do makes it seem like they use the two preference settings to create a ratio, and that ratio is used to scale monospace text. That’s not actually what’s happening, but it looks that way at first. To see what I mean, let’s consider:

span {font-family: monospace; font-size: 2em;}

<p>This is a 'p' with a <span>'span'</span> inside.</p>

Again: in the absence of other author styles, what should be the computed font-size of the span element?

The answer: “It depends, but most likely 26px as long as we aren’t talking about Opera 10 or IE8. If it is one of those two, then most likely 32px.” Why? Because the resizing browsers see the font-size: 2em; declaration as “twice medium” and twice 13 is 26. Opera 10 and IE8, as previously established, don’t do the resizing. Or else they simply interpret medium as being equal to the proportional font size preference setting. Whatever.

Okay. So what all this means is that in many browsers, you can declare that an element’s font size should be twice the size of its parent’s and have it actually be 1.625 times the size — or, if you want to look at it another way, 0.8125 times the size you expected it to be. The 0.8125 comes from 26/32, which of course reduces to 13/16. If you were to adjust your browser’s preferences so the monospace setting is “15”, then monospace fonts would be 0.9375 (15/16) times the expected size.

But — and here’s where things get really fun — this is not always so. See, you may not have run into this problem if you’ve been declaring specific font families with no generic fallback. Consider this variation (note that I dropped back to 1em for the font-size):

span {font-family: "Courier New"; font-size: 1em;}

<p>This is a 'p' with a <span>'span'</span> inside.</p>

This time, in every one of the five browsers I mentioned before, assuming the browser defaults, the computed (and rendered) font-size of the span will be 16px. Not 13px. And the only difference is that we switched from a generic font family to a specific one.

“Hey presto!” you shout. “We’ll just tack the generic family on the end there and be right as rain!” Sadly, no. For if you do this:

span {font-family: "Courier New", monospace; font-size: 1em;}

<p>This is a 'p' with a <span>'span'</span> inside.</p>

…then the answer to the question I keep asking will be: “It depends, but given browser defaults it will be 16px, unless we’re talking about Safari. In that case, it’s 13px.”

Really. Alone among the browsers I tested, Safari goes back to doing the resizing when you provide a generic fallback to your specific family. Or even multiple families. Do your best to make sure the user at least gets a fixed-width font, and you get a size smaller than you’d intended. (You can get the back story on this in a late-2006 post on the Surfin’ Safari blog.)

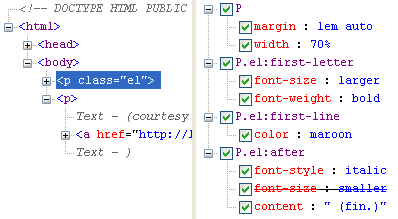

So what do we do? Get creative. That’s what the ARIA folks did in their specification’s style sheet, where they declare two font stacks: the first with a generic fallback, and the second without it. That works, but it’s ugly. I didn’t like that at all. And then, halfway through writing up this post, a fix came to me like a shot in the dark. Check this out:

span {font-family: "Courier New", monospace, serif; font-size: 1em;}

<p>This is a 'p' with a <span>'span'</span> inside.</p>

This time around, the answer is: “It depends, but given browser defaults, 16px.”

Really! Even in Safari! And in all tested browsers, it falls back to a generic monospace font at the requested size even if the specific family (or families) we declare aren’t available! This can be verified by altering the specific font family to something that doesn’t actually exist:

span {font-family: "Corier Neu", monospace, serif; font-size: 1em;}

<p>This is a 'p' with a <span>'span'</span> inside.</p>

Monospacey goodness at the intended, parent-matching size. It’s enough to make a body believe in monotheism.

Since I generally assume that anything I devise was already invented by someone else, I went Googling for prior art. And wouldn’t you know it, the Wikipedia folks had worked it out around the end of last year. This, of course, supports my contention that Wikipedia is the new Steve Allen. I also found some claims that ending the font stack with monospace, monospace would have the same effect, but that wasn’t borne out in my testing. Perhaps it worked in older versions of browsers but no longer does.

I did leave out another way to make monospaced fonts behave as expected, which you may have already figured out from the preceding: declare the font-size for any parent of a monospaced element to be a length value, along the lines of body {font-size: 12px;}. That will pass the length value down the document tree to the monospaced element via inheritance, which will use it without resizing it in every browser I tested. Though you may have heard that page zooming makes pixel-sized text okay, I’m not really convinced. Not yet. There are too many people who don’t know how to zoom, and too many whose browsers aren’t advanced enough to zoom pages. Even in page-zooming browsers, there are problems with pixel text. So I’m still on the ems-and-percentages bandwagon.

In fact, there are a fair number of details and extra browser oddities that I left out of this, as it’s already way more than long enough, and besides you don’t really want to hear the gory details of manually stepping through 37 different preferences settings just to verify a theory. Plus you already heard about the font-size rounding investigation that spawned off of this one, about halfway through. I think that’s more than enough for the time being.

I should also lay down a caveat: it’s possible that this behavior will be interpreted as a bug by the Safari team and “fixed”, if that’s the word I want, in a future release. I really hope not — and if they’re looking for ways to improve how they handle monospace font sizing, I have a few suggestions — but it is possible. Adjust your expectations accordingly.

And with that, I’m going to stop now. I hope this will be useful to you, either now or in the future.