While I was in Florida with my family visiting both sets of parents, Tristan Nitot published an article titled “How Microsoft can support CSS2 without breaking the Web“. In it, Tristan points to a comment made by Gary Schare, Director of Windows Product Management at Microsoft, which was:

We could change the CSS support and many other standards elements within the browser rendering platform. But in doing so, we would also potentially break a lot of things.

(from Microsoft Windows Exec Talks IE, Firefox)

Tristan then goes on to refute this line of thinking. Generally speaking, I’m entirely in agreement with him. (As a disclaimer, Tristan and I worked together as members of the Netscape Standards Evangelism Team, and Tristan asked me for feedback on his article before it was published.)

Here’s the thing: in the Windows world, Explorer already significantly upgraded its standards support four different times. The most recent such upgrade was called IE6. That was the version that first added DOCTYPE switching to IE/Win. At that time, there were a great many changes made to the standards support, nearly every one for the better. For example, in standards mode, you could no longer throw around unitless numbers and have them interpreted as pixels, because that violated the CSS specification. You couldn’t set a height or width for an inline non-replaced element, because that too was incorrect. The interpretation of font-size keywords was changed to reflect the CSS specification instead of the HTML font-sizing regime. The box model was altered to follow CSS instead of the old IE way. In short, there was all kinds of stuff in there that would “break a lot of things”.

The Web rather steadfastly declined to be broken. Oh, sure, there were pages whose layout was altered—not many, thanks to the way DOCTYPE switching was implemented, but they were out there. Anyone who was relying on the IE/Win way of doing things but used a DOCTYPE that triggered standards mode (say, for example, a HTML 4.01 Transitional DOCTYPE with URI) ended up with a “broken” page. These problems were fixed by their authors, and that was that. I remember a number of forum posts about how “IE6 broke my design”, and the posts that helped those authors address the problem. In the case of old, unmaintained pages, they stayed broken, but odds are that next to nobody cared. Regardless, it isn’t exactly a point of major concern on any radars I’ve seen in the last three years.

Furthermore, IE6 fixed a number of parsing bugs that existed in previous versions. One of those was the bug on which Tantek Çelik’s “Box Model Hack” depended. However, the parsing bug was fixed in both quirks and standards modes, so the BMH utterly failed to work in IE6 no matter what DOCTYPE you used. That actually did break quite a few layouts, if I remember correctly. I also remember the day I discovered that they’d fixed the parsing bug in both standards and quirks modes. I swore at my monitor for a moment, and then actually thought about it. I realized that the inconvenience of removing a few CSS hacks, or at worst changing to different hacks, was a pittance to pay in comparison to the advances IE6 had made in terms of increased standards support.

So I fixed a few style sheets, tossed a hack out of my mental toolbox, and got on with my life. I contend that exactly the same thing would happen if a service pack were to add increased standards support to IE.

This is particularly true given that most of what IE should add would be, well, additions. As in, things that IE doesn’t even try to support now, and so almost nobody uses them. Think generated content. Think attribute selectors. Think fixed positioning. These are all things that, if they were added to IE, would break almost no pages at all. In fact, they’d make a small number of pages work better in IE.

For that incredibly small number of pages that would break (for whatever value of “break” you care to name) with improved standards support in IE6, I’m willing to bet that nearly all of them would get fixed right away. Why? Because they would be pages maintained by authors who actually want to use standards and care about doing things right.

Now, there is one area where I think the IE team would have to be careful about adding support, and that’s selectors. A lot of hide-from-IE CSS hacks these days are based on its failure to support the child selector; in fact, I use these a few places in the S5 style sheets. It is possible that adding support for child selectors to IE6 would be more harmful than beneficial. I say it’s possible because I don’t know. Nobody does—but Microsoft of all organizations has the ability to find out, and to act accordingly. They have the funding, the personnel, the skills, and the customer base. As Tristan said:

In its short, 2 1/2 year life, the Netscape Evangelism team helped literally thousands of authors and administrators of web sites around the world to improve their support for the W3C DOM and CSS Standards. If such a small group with limited resources can help change the web, imagine what Microsoft could do with its resources if it only tried.

Indeed.

Granted, the net stands still for no one, not even Microsoft. There have already been, and continue to be, efforts to graft better standards support onto IE despite itself: projects like PNG transparency fixes, whatever:hover, and IE7 take Microsoft’s proprietary behaviors and use them to make it easier to use open standards. (I adore the poetry of that.) The people behind those projects are already doing what Microsoft is apparently afraid to do, and they demonstrate why improving standards does not mean breaking the Web.

There’s one other point to consider. If IE/Win improved its standards support in any meaningful way, believe me when I say that the news would be shouted from the Web site of every standards advocate in the known universe. Nobody responsible for standards-oriented pages could avoid hearing about it. Any problems would be quickly explained, and adjustments made. Life would not only go on, but be better for developers and designers.

To sum up: the “more standards will break stuff” argument just doesn’t fly any more. Microsoft can figure out what to do that won’t break pages, and there’s a ton of things that are new-to-IE, the implementation of which will no more break pages than did the image toolbar. In cases that might cause breakage, Microsoft can determine—with community help, if they were to ask for it—how to minimize breakage while maximizing benefit. To claim that possible Web page breakage prevents Microsoft from increasing standards support makes about as much sense as to claim that possible program breakage prevents them from ever changing or improving their operating system.

Despite this, I don’t have much hope that we’ll see any improvements before Longhorn debuts. I think that’s a shame, because I remember when the IE team was gung-ho about standards. There were a number of very smart people who understood why standards were important, and were committed to doing their best to support standards in IE—not just on the Macintosh, but for Windows as well.

I do hope for Microsoft’s sake that those days return. Because the Web continues to move, and if they just stand there promising that everything will be better in Longhorn, they may well find themselves left behind.

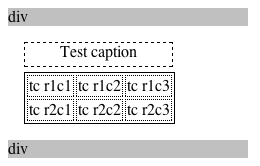

In Safari, you see, the caption’s element box is basically made a part of the table box. It sits, effectively, between the top table border and the top margin. That allows the caption’s width to inherently match the width of the table itself, and causes any top margin given to the table to sit above the caption. Makes sense, right? It certainly did to me.

In Safari, you see, the caption’s element box is basically made a part of the table box. It sits, effectively, between the top table border and the top margin. That allows the caption’s width to inherently match the width of the table itself, and causes any top margin given to the table to sit above the caption. Makes sense, right? It certainly did to me.

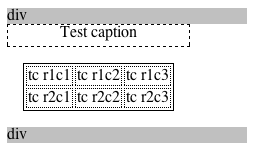

This is the behavior evinced by Firefox 1.0, and as unintuitive as it might be, it’s what the specification demands.

This is the behavior evinced by Firefox 1.0, and as unintuitive as it might be, it’s what the specification demands.