25 Years of CSS

Published 2 years, 11 months pastIt was the morning of Tuesday, May 7th and I was sitting in the Ambroisie conference room of the CNIT in Paris, France having my mind repeatedly blown by an up-and-coming web technology called “Cascading Style Sheets”, 25 years ago this month.

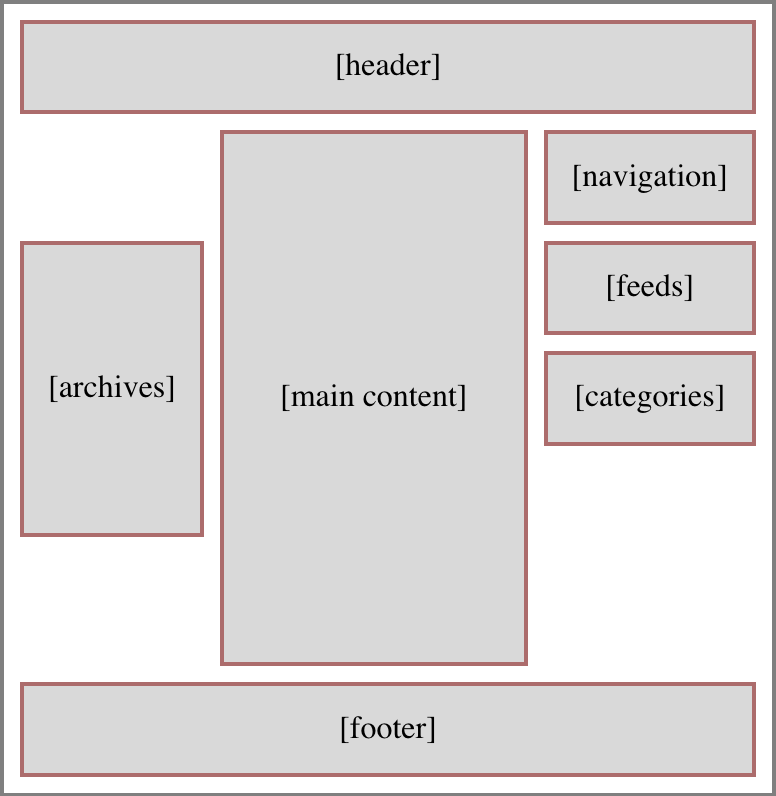

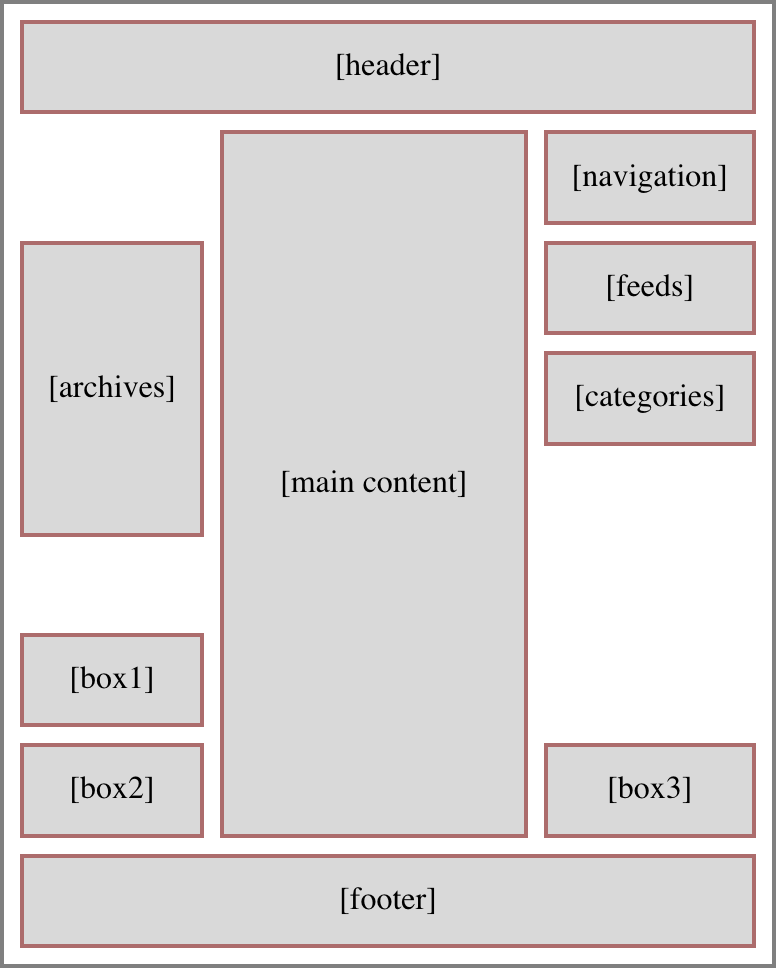

I’d been the Webmaster at Case Western Reserve University for just over two years at that point, and although I was aware of table-driven layout, I’d resisted using it for the main campus site. All those table tags just felt… wrong. Icky. And yet, I could readily see how not using tables hampered my layout options. I’d been holding out for something better, but increasingly unsure how much longer I could wait.

Having successfully talked the university into paying my way to Paris to attend WWW5, partly by having a paper accepted for presentation, I was now sitting in the W3C track of the conference, seeing examples of CSS working in a browser, and it just felt… right. When I saw a single word turned a rich blue and 100-point size with just a single element and a few simple rules, I was utterly hooked. I still remember the buzzing tingle of excitement that encircled my head as I felt like I was seeing a real shift in the web’s power, a major leap forward, and exactly what I’d been holding out for.

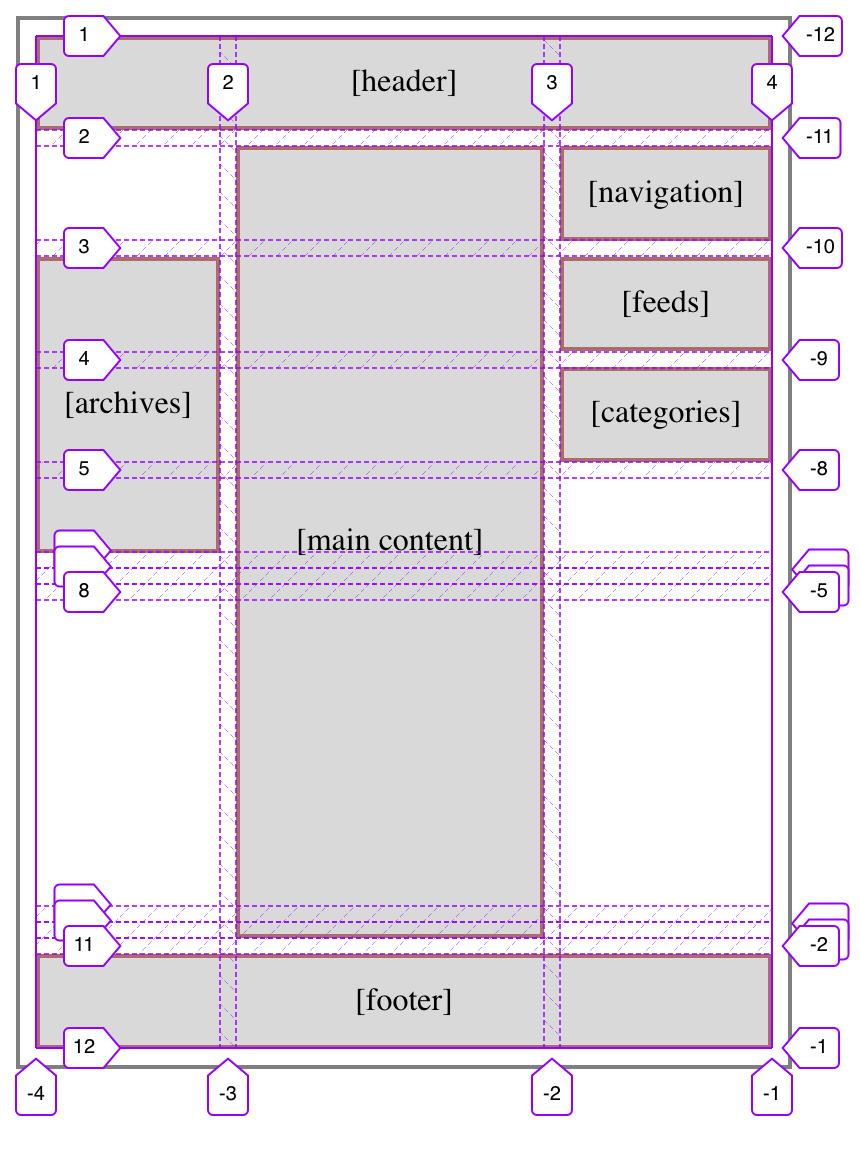

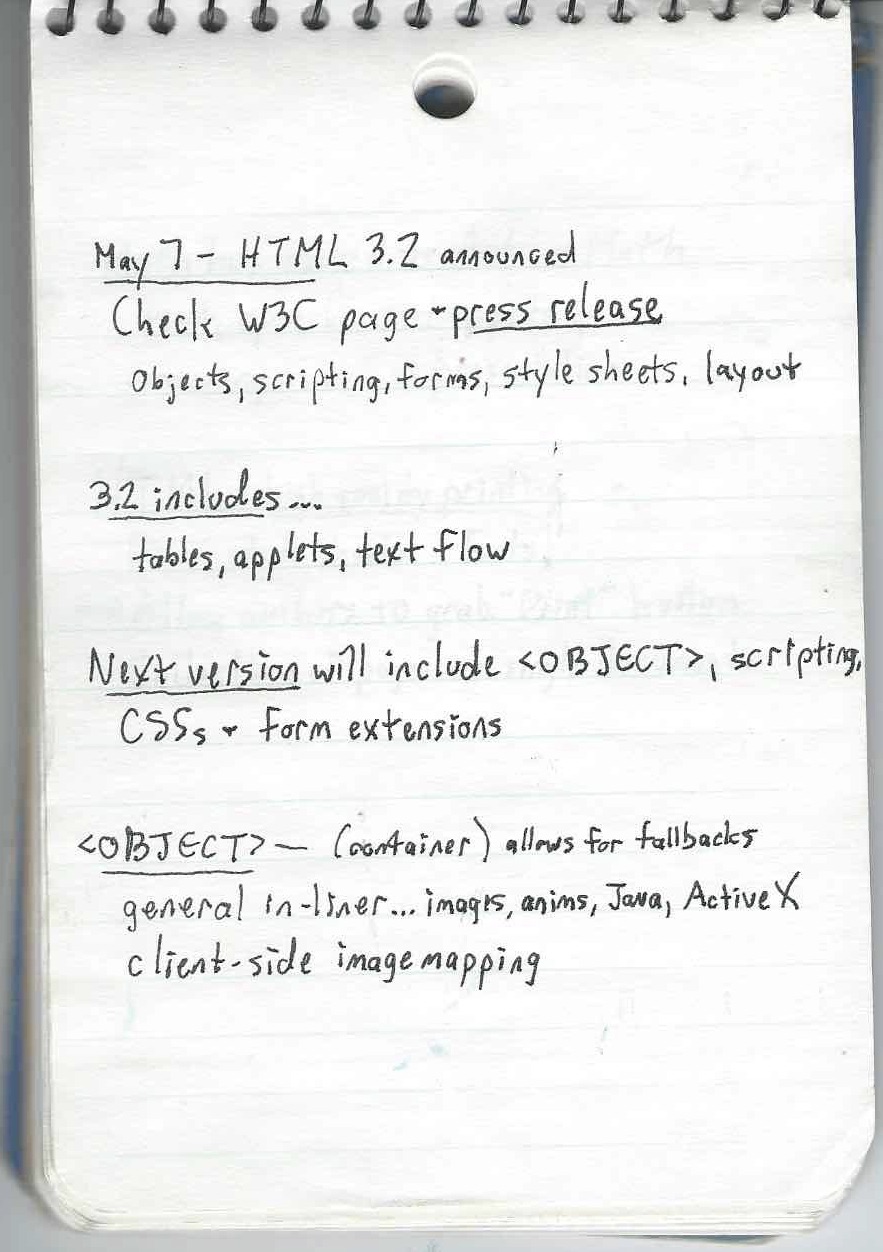

Looking back at my hand-written notes (laptops were heavy, bulky, battery-poor, and expensive in those days, so I didn’t bother taking one with me) from the conference, which I still have, I find a lot that interests me. HTTP 1.1 and HTML 3.2 were announced, or at least explained in detail, at that conference. I took several notes on the brand-new <OBJECT> element and wrote “CENTER is in!”, which I think was an expression of excitement. Ah, to be so young and foolish again.

There are other tidbits: a claim that “standards will trail innovation” — something that I feel has really only happened in the past decade or so — and that “Math has moved to ActiveMath”, the latter of which is a term I freely admit I not only forgot, but still can’t recall in any way whatsoever.

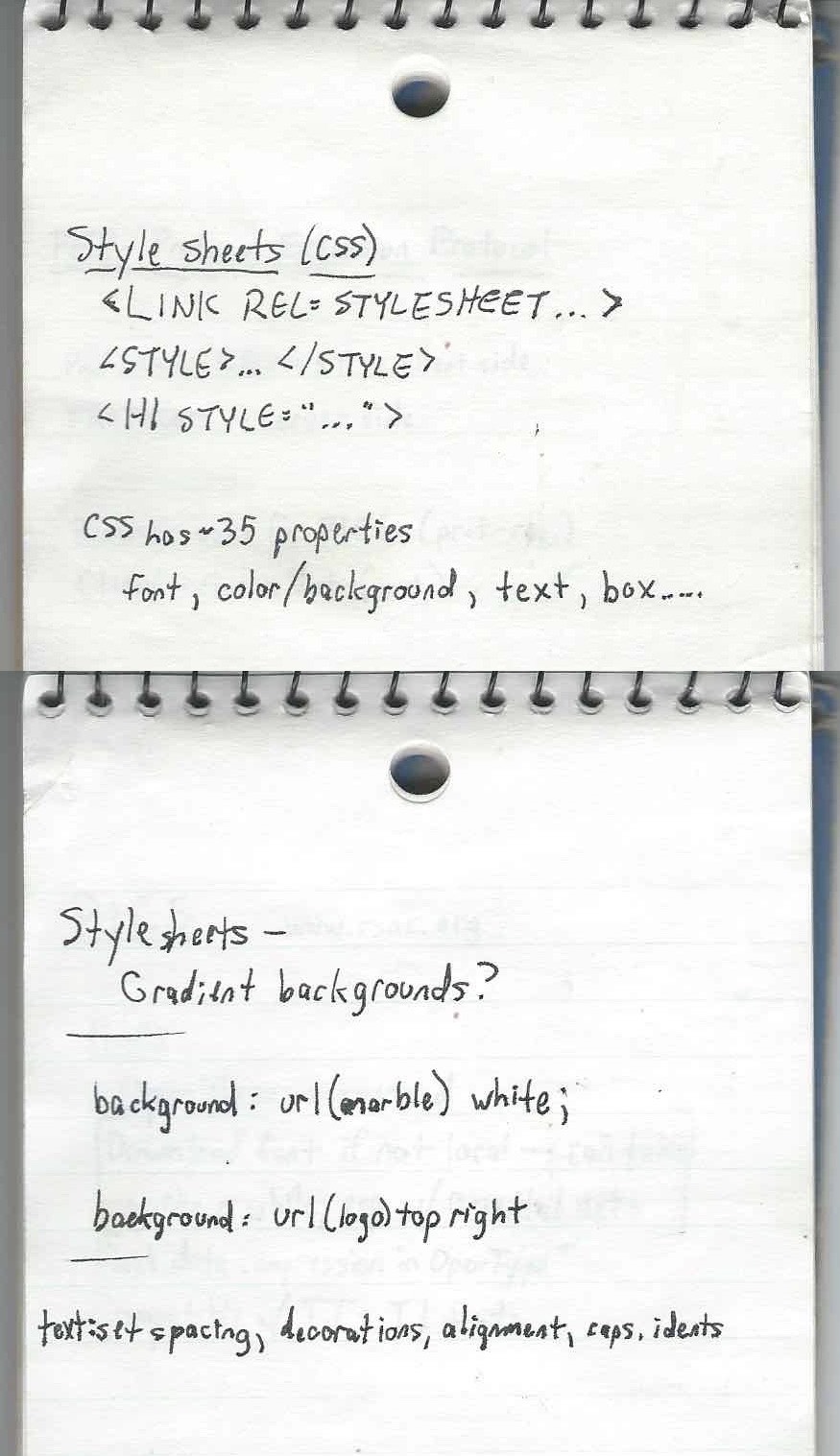

But I did record that CSS had about 35 properties, and that you could associate it with markup using <LINK REL=STYLESHEET>, <STYLE>…</STYLE>, or <H1 STYLE="…">. There’s a question — “Gradient backgrounds?” — that I can’t remember any longer if it was a note to myself to check later, or something that was floated as a possibility during the talk. I did take notes on image backgrounds, text spacing, indents (which I managed to misspell), and more.

What I didn’t know at the time was that CSS was still largely vaporware. Implementations were coming, sure, but the demos I’d seen were very narrowly chosen and browser support was minimal at best, not to mention wildly inconsistent. I didn’t discover any of this until I got back home and started experimenting with the language. With a printed copy of the CSS1 specification next to me, I kept trying things that seemed like they should work, and they didn’t. It didn’t matter if I was using the market-dominating behemoth that was Netscape Navigator or the scrappy, fringe-niche new kid Internet Explorer: very little seemed to line up with the specification, and almost nothing worked consistently across the browsers.

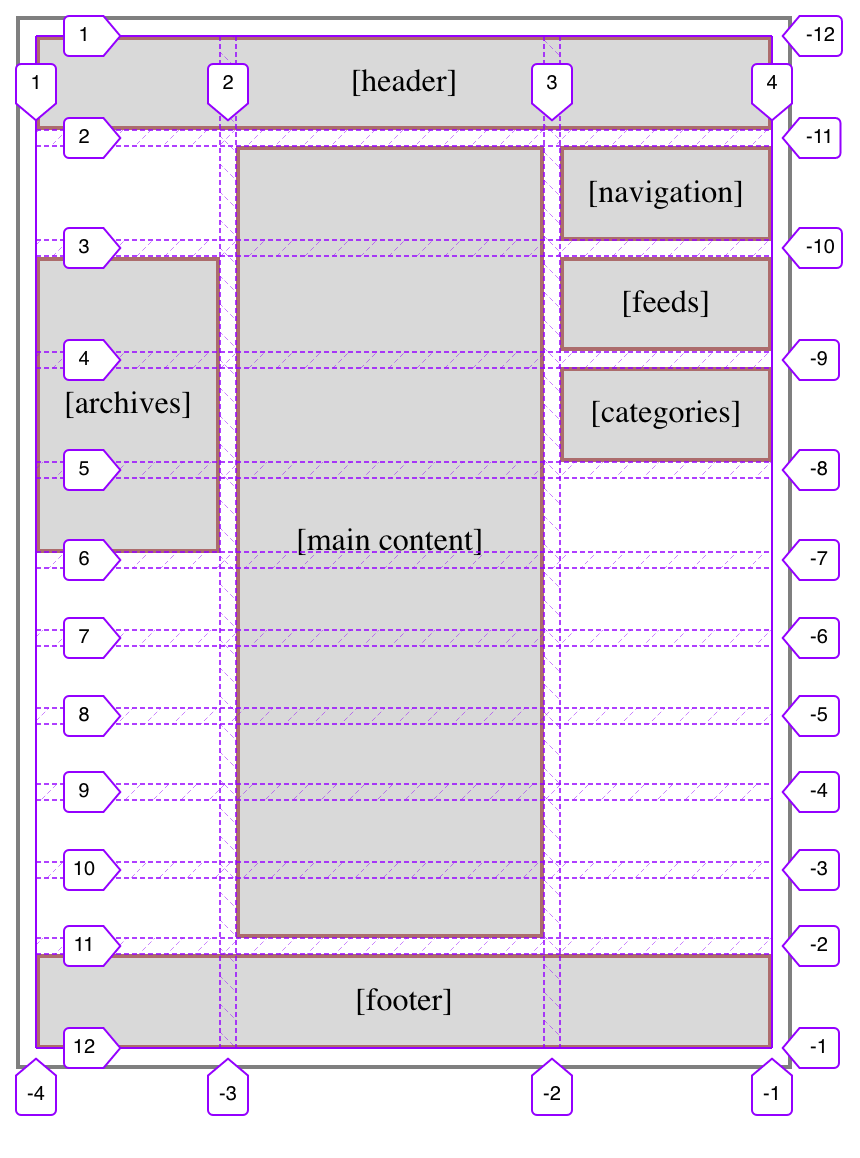

So I started creating little test pages, tackling a single property on each page with one test per value (or value type), each just a simple assertion of what should be rendered along with a copy of the CSS used on the page. Over time, my completionist streak drove me to expand this smattering of tests to cover everything in CSS1, and the perfectionist in me put in the effort to make it easy to navigate. That way, when a new browser version came out, I could run it through the whole suite of tests and see what had changed and make note of it.

Eventually, those tests became the CSS1 Test Suite, and the way it looks today is pretty much how I built it. Some tests were expanded, revised, and added, plus it eventually all got poured into a basic test harness that I think someone else wrote, but most of the tests — and the overall visual design — were my work, color-blindness insensitivity and all. Those tests are basically what got me into the Working Group as an Invited Expert, way back in the day.

Before that happened, though, with all those tests in hand, I was able to compile CSS browser support information into a big color-coded table, which I published on the CWRU web site (remember, I was Webmaster) and made freely available to all. The support data was stored in a large FileMaker Pro database, with custom dropdown fields to enter the Y/N/P/B values and lots of fields for me to enter template fragments so that I could export to HTML. That support chart eventually migrated to the late Web Review, where it came to be known as “the Mastergrid”, a term I find funny in retrospect because grid layout was still two decades in the future, and anyway, it was just a large and heavily styled data table. Because I wasn’t against tables for tabular data. I just didn’t like the idea of using them solely for layout purposes.

You can see one of the later versions of Mastergrid in the Wayback Machine, with its heavily classed and yet still endearingly clumsy markup. My work maintaining the Mastergrid, and articles I wrote for Web Review, led to my first book for O’Reilly (currently in its fourth edition), which led to my being asked to write other books and speak at conferences, which led to my deciding to co-found a conference… and a number of other things besides.

And it all kicked off 25 years ago this month in a conference room in Paris, May 7th, 1996. What a journey it’s been. I wonder now, in the latter half of my life, what CSS — what the web itself — will look like in another 25 years.