Posts in the Web Category

What Comes Next…

Published 9 years, 2 months past

There is a documentary about the history of the web. It’s an hour long, and now it’s free to watch.

Also, I’m in it — a fair amount, it turns out. Please do not let this dissuade you from watching it.

I’m blogging about this because there’s a little bit of a backstory. Jeffrey and I were backers of the film during its crowdfunding campaign. At that point, Jeffrey had been already interviewed for the film, but even beside that, we really wanted the film to exist in the world. So much of the history of our craft has been lost, or simply untold. So we put some of AEA’s resources into supporting the project, and were glad to see it meet its funding goal. So, you know, full disclosure and all: I’m a backer of the film, and I’m in it. Jeffrey, too.

In fact, I wouldn’t be surprised to find out most of the people who appear in the film were also backers of the film. This probably makes it sound like people paid to be featured, but nothing could be further from the truth. It’s the exact opposite: the people featured in the film are featured because they’re the kind of people who would badly want to see such a thing exist in the first place, and lend material support to the effort. They’re all people who truly love the craft and want to see it documented, explained, and shared with as many people as possible. The kind of people who learned from others, and in turn taught others, freely sharing what they knew. In some cases, paying out of pocket to share what they knew, in hopes that the sharing would help someone. I think that ethos comes through bright and clear in the film.

If you want to understand the heart of the web, understand that. It was designed and built and fundamentally shaped from its earliest days by people who wanted it to be open and free and accessible to anyone, whether as a consumer or a creator. Those were the founding principles. They shape every aspect of the web we know, for good or ill or otherwise.

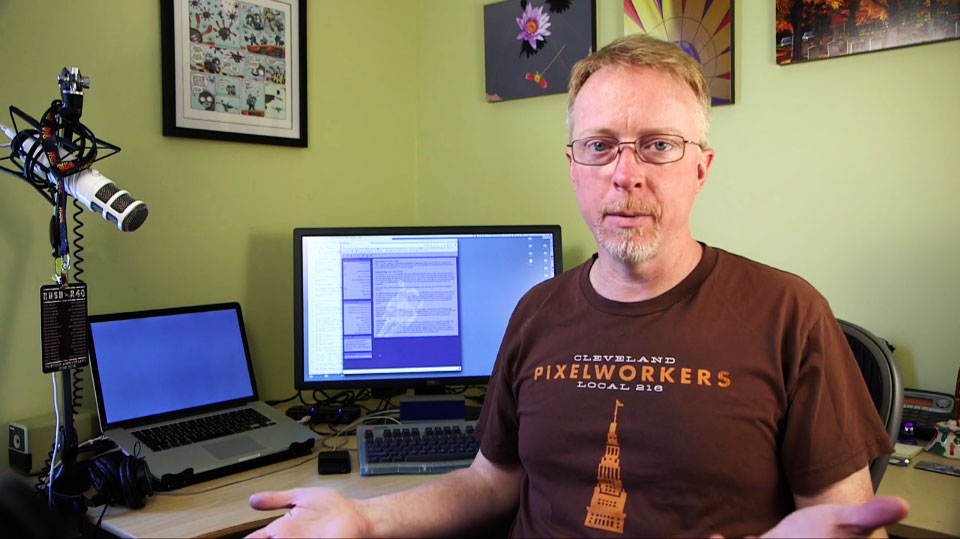

Some time after the film was crowdfunded — about a year and a half, I think — Matt, the film’s director, editor, and all-around prime mover, drove up from his office in Pittsburgh to my office in Cleveland to shoot some of the last segments to be recorded. So he asked me the questions he still wanted someone to answer, or that had arisen as he’d started editing all the other interviews. Thus I show up a lot in the first half of the film, talking about the early days of the web, and am mostly absent in the second half, as the younger crowd talks about the great stuff that happened as the web matured. Which is proper, I think.

But! I hasten to add, there are way, way smarter and better-spoken people in the film than me, all the way through, sketching out the path this field took and what makes the web so incredibly compelling and powerful even today. It’s company I’m honored and humbled to be part of. If you can spare an hour, say a lunch break, I highly recommend you devote it to What Comes Next is the Future.

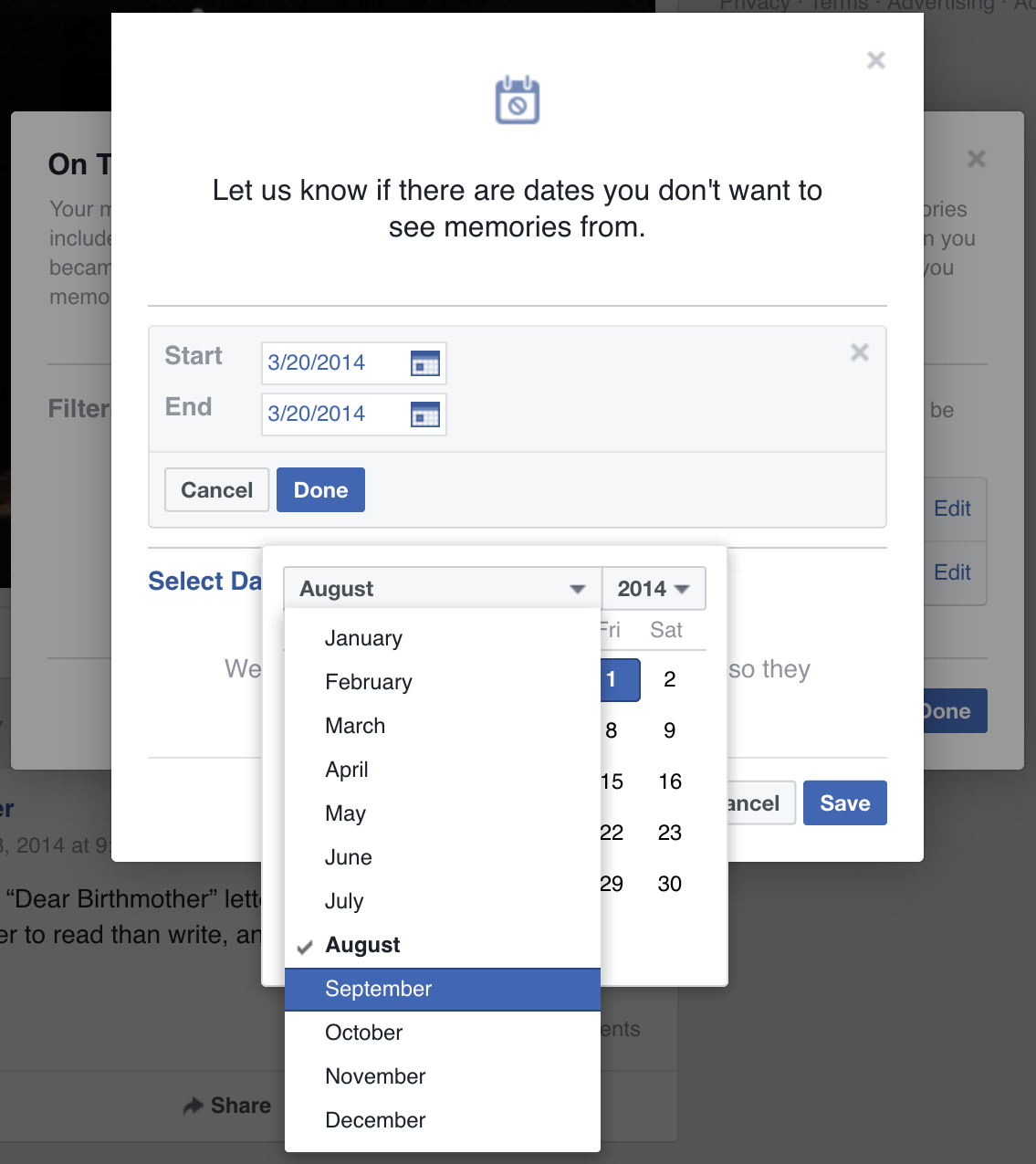

Not On This Day

Published 9 years, 2 months pastSuppose you use Facebook (statistically, odds are at least 1 in 5 that you do). Further, suppose you have a period of your life, or even more than one, that you’d rather not be mined by Facebook’s “On This Day” feature. Here’s how to set a blackout for any period(s) of time.

- Go to facebook.com/onthisday in a web browser while logged into Facebook. Said browser can be either desktop or mobile.

- In a desktop web browser, click the “Preferences” button in the upper right quadrant of the page, to the right edge of the On This Day masthead. In a mobile web browser, tap the gear icon in the upper right, then tap “Preferences”.

- Select the “Dates” line (on desktop, you have to click the “Edit” link on the right).

- Now select the “Select Dates” link that looks like a section heading, but is actually a point of interaction.

- Select start and end dates, in that order (see below). On desktop you can type into the boxes or use the popup calendars; on mobile, you get date wheels.

- Select “Done” (desktop) or “Add” (mobile).

- If you want to add more date ranges to filter out, go back to the “Select Dates” step again and work forward.

- Once you’re done, select “Save”.

- To finish setting preferences, select “Done”.

…and that’s it, he said dryly.

Should you want to effectively disable On This Day, you can set up a date range of January 1, 1900 to December 31, 2099. I couldn’t go past 2099 in my testing — according to the error message, anything from 2100 on is an “invalid date”. I also discovered that setting a start date will always reset the end date to the new start date, so make sure to set your start date first and your end date second.

You might have seen that you can also filter out specific people. The process there is similar, except you type names to find accounts to filter out instead of using date pickers.

So that’s it. The preferences aren’t easy to find, but they are there. I’d be a lot happier if Facebook let you pick a given date and applied it to all years — thus allowing you to block out the birthday of an ex-spouse, or the wedding anniversary of a now-defunct marriage, for example. I’d be happier still if they surfaced these preferences more readily; say, prompting you with a date-exclusion option whenever you tell them you don’t want to see a given memory in your timeline. I don’t mind writing how-to guides to help other people, but I do sometimes mind that their existence feels necessary, if you follow me there.

A note for the future: this guide was accurate as of the date of publication. If you’re reading it some time later, especially if it’s been several months or years, bear in mind that things may have changed in the meantime. In that case, please feel free to leave a comment indicating there’s been a change, so I can update the guide. Thanks!

CSS Grid!

Published 9 years, 3 months pastThe Grid code is coming! The Grid code is coming! It’s really, finally coming to a browser near you! Woohooooo!

Whoa, there. What’s all the hubbub, bub?

CSS Grid is going to become supported-by-default in Chrome and Firefox in March of 2017. Specifically, Mozilla will ship it in Firefox 52, scheduled for March 7th. Due to the timing of their making Grid enabled-by-default in Chrome Canary, it appears Google will ship it in Chrome 57, scheduled for March 14th. In each case, once the support is enabled by default in the public-release channels — that is to say, the “evergreen” browser releases that the general public uses — every bit of Grid support now in place in the developer editions of the browsers will become exposed in the public releases. Anything Grid will Just Start Working™®©.

Are those dates an ironclad guarantee?

Heck no. Surprise problems could cause a pushback to a later release. The release schedule could shift. The sun could explode. But we know the browsers already have running code for Grid, and when they mark something as ready for public release, it usually gets released to the public on schedule.

So Grid support in March, huh?

Yep!

How long until I can actually use Grid, then? Two or three years?

March 2017. So about four months from now.

But it won’t be universally supported then!

Rounded corners aren’t universally supported even now, but I bet you’ve used them.

Now you’re just being disingenuous.

Look, I get it. Base layout’s a little different than shaving pixels off corners, it’s true. If you have a huge IE9 user base, converting everything to Grid, and only Grid, might be a bit much. But I’m guessing that you do have a layout that functions in older browsers, yes?

Of course.

Then my original answer stands: March 2017. Because any browsers that understand Grid will also understand @supports(), and you can use that to have a Grid layout for Grid-enabled browsers while still feeding a float-and-inline-block layout to browsers that don’t understand Grid. Jen Simmons wrote a comprehensive article about @supports(), and I wrote a short article demonstrating its use to add layout enhancements. The same principles will apply with Grid: you can set up downlevel rules, and then encapsulate the hot new rules in @supports(). You can retroactively enhance the layouts you already have, or take that approach with any new designs.

Writing two different layouts for the same page doesn’t sound like a good use of my time.

I get that too. Look at it this way: at some point, you’re going to have to learn Grid. Why not learn it on the job, experimenting with layouts you already understand and know how you want to have behave, instead of having to set aside extra time to learn it in a vacuum using example files that have nothing to do with your work? You’ll be able to take it at your own pace, build up a new set of instincts, and future-proof your work.

Can’t I just wait until someone creates a framework for me?

You could, except here’s the thing: as Jen Simmons has observed, Grid is a framework. Using a framework to abstract a framework seems inefficient at best. I mean, sure, people are going to do it. There will be Gridstraps and GAMLs and 1280.gses and what have you. And when those are out, if you decide to use one, you’ll have spend time and energy learning how it works. I recommend investing that time in learning Grid Actual, so that you can build your own layouts and not be constrained by the assumptions that are inevitably baked into frameworks.

Grid sounds like tables 2.0. I thought we all agreed tables for layout were a bad idea.

We agreed table markup for layout was a bad idea, particularly because at the time it was popular, it required massive structural hacks just to get borders around boxes, never mind rounded corners. The objection was that it took 50KB of HTML tags and three server calls just to do anything, and 100 times that to set up a whole page’s layout, plus table markup locked everything into a very precise source order that played merry hell with any concept of accessible, searchable content. The objection wasn’t to the visual result. It was to what it took to get those results.

With Grid, you get the ability to take simple, accessible markup, and lay it out pretty much however you want. You can put the last element in the source first in layout, for example. You can switch a couple of adjacent bits of the page. Questions like “how do I order these elements to get them to lay out right?” become a thing of the past. You order them properly, and then lay them out. It’s the closest we’ve ever gotten to a clean separation between structure and presentation.

Not only that, but thanks to CSS transforms, clipping paths, float shapes, and more, you don’t have to make everything into a perfectly-edged grid layout. There is so much room for visual creativity, you can’t even imagine. I can’t even imagine. Nobody can.

So Grid solves every single layout question we’ve ever had, huh? Layout Nerdvana for all?

Oh, no, there are still things missing. Subgrid didn’t make it into these releases, so there will still be some gridlike layouts that seem like they should be simple, but will actually be difficult or impossible. You can’t style a grid cell or area directly; you have to have a markup element of some sort to hang there and style. All grid areas and cells have to be rectangular — you can’t have an L-shaped area, for example. Grid gaps (“gutters”) can only be of uniform size on a given axis, very much like border-spacing in table CSS.

You can usually fake your way around these limitations, but they’re still limitations, at least for now. And yeah, there will probably be bugs found. If not bugs, probably unexpected use cases that the spec doesn’t adequately cover. But a lot of people have worked really hard over an extended period of time on stamping out bugs and supporting a variety of use cases. This is solid work, and it’s going to ship in that state.

What happens if Firefox or Chrome pushes Grid back a release or two, but the other ships on schedule?

In that case, it will take a little longer for your @supports()-encapsulated Grid rules to be recognized by the tardy browser. No big deal. The same applies to MS Edge, which hasn’t caught up to the new Grid syntax even though it was the first to ship a Grid implementation — with different rules, all behind prefixes. Once Edge gets wise to the new syntax and behaviors, your CSS will just start working there, same as it did in Firefox and Chrome and any other browser that adds Grid.

All right, so where can I go to learn how to use it?

There are several good resources, with more coming online even now. Here are just a few:

- The Experimental Layout Lab of Jen Simmons — great for seeing layout examples in action using a variety of new technologies. If you’re laser-focused on just Grid, then start with example #7, “Image Gallery Study”, but the whole site is worth exploring. Bonus: make sure to responsively test the top of the page, which has some great Grid-driven rearrangements as the page gets more narrow.

- Rachel Andrews’ Grid By Example — a large and growing collection of examples, resources, tutorials, and more. There’s a whole section titled “Learn Grid Layout” that’s further broken up into sections like “UI Patterns” and “Video tutorial”.

- CSS-Tricks’ A Complete Guide to Grid — a boiled-down, pared-down, no-nonsense distillation of Grid properties and values. It might be a bit bewildering if you’re new to Grid, but it’s the kind of resource you’ll probably come back to again and again as you’re getting familiar with Grid.

- CSS Grid Layout specification — if all else fails, you can always go to the source, Luke.

But remember! If you hit these sites before March 2017, you’ll need to make sure you have Grid support enabled in your browser so that you can make sense of the examples (not to mention anything you might create yourself). Igalia has a brief and handy how-to page at Enable CSS Grid Layout, and Rachel also has a Browsers page with more information.

I’ve been hurt by layout promises before, and I’m afraid to trust.

I feel you. Oh, do I feel you. But this really looks like the real thing. It’s coming. Get ready.

Invisible Airwaves

Published 9 years, 10 months pastAll of a sudden, I’m on three different podcasts that released within the last week. Check ‘em out:

- The Web Ahead #115 — recorded LIVE! at An Event Apart Nashville, I joined Rachel Andrew, Jeffrey Zeldman, and host Jen Simmons for an hour-plus look at the present and future of web design and web design technologies, featuring a number of really sharp questions submitted by the audience as we talked. We got Nostradamic with this one, so warm up the claim chowder pots!

- User Defenders #20 — Sara and I talked with host Jason Ogle for just over an hour about Design for Real Life, digging deep into the themes and our intentions. Jason really brought great questions from having just read the book, and I feel like Sara and I kept our answers focused and compact.

- The Big Web Show #144 — Jeffrey and I talked for just under an hour about Design for Real Life and the themes of my AEA talk this year. This one’s more of a ramble between two friends and colleagues, so if you prefer conversation a little looser, this one’s for you.

Share and enjoy!

Design for Real Life

Published 10 years, 5 days pastOn March 8th, 2016 — just eight days from the day I’m writing this — Design for Real Life will be available from A Book Apart. My co-author Sara Wachter-Boettcher and I are really looking forward to getting it into people’s hands.

The usual fashion is to say something like “getting it into people’s hands at long last”, but in this case, that’s not really how it went down. Just over a year ago now, Sara published “Personal Histories”, and it was a revelation. In her post, I could see the other half of the book that was developing in my head, a book that was growing out of “Designing for Crisis” and “Inadvertent Algorithmic Cruelty”. So I emailed Sara and opened with:

Your post was like a bolt of lightning for me. In the same way the Year in Review thing opened my eyes to what lay beyond “Designing for Crisis”, your post opened my eyes to how far that land beyond reaches.

After research and some intense discussions, we started writing in the spring of 2015, and finished before summer was over. Fall of 2015 was devoted to rewrites, revisions, additions, and editing. Winter 2015-2016 was spent in collaborative editorial and production work by the amazing team at A Book Apart. And now…here we are. The book is just a week away from being in people’s hands.

To celebrate, Sara and I will be hosting, with incredibly generous support from A Book Apart and PhillyCHI, a launch party at Frankford Hall in Philadelphia. We’ll be providing some munchies, some tasty adult beverages, and there will be giveaways of both paper and digital copies of the book. We’d love to see you there! If you can make it, please do RSVP at that link, so we know how much food to order.

We chose Philadelphia as the site for our launch party for a few reasons. For one, Sara lives there, so only one of us had to travel. But to me, it brings some very personal histories full circle, because Philadelphia is where this really all got started. It’s where Rebecca first went to be treated, where she was given the best possible shot at life, and where I started to notice the failures and successes of user experience design when it collided with the stresses of real life.

In a number of ways, this book has been a labor of love. The most important, I think, is the love Sara and I have for our field, and how we would love to see it become more humane — really, more human. That’s why we packed the book not just with examples of good and bad design choices, but of how we can do better. The whole second part of the book is about how to take the principles we explore in the first part and put them to work right now — not by throwing out your current process and replacing it with a whole new, but by bringing them into your existing practice. It’s very much about enhancing what you already do.

It’s been an intense process, both emotionally and work-wise. We pushed as hard as we could to get this to you as soon as we could. Now the time is almost here. We’re really looking forward to hearing what you think of it.

Designing for Crisis, Design for Real Life

Published 10 years, 1 month pastBack in October of 2014, at An Event Apart Orlando, I returned to public speaking with “Designing for Crisis”, my first steps toward illuminating how and why design needs to consider more than just the usual use cases. I continued refining and delivering that talk throughout 2015, and it was recorded in October 2015 at An Event Apart Austin. As of late last week, you can see the entire talk for free.

There were a lot of strange confluences that went into that talk, some of them horrific, others just remarkable. One that stands out for me, as I look at that screenshot, is how a few years ago, Jared Spool gave a talk at AEA where he discussed the GE Adventure Series, in a segment that never failed to choke me up (and often choked up Jared). I remember being completely floored by that example, and at one point, based solely on what he’d said about the GE Adventure Series, I remarked to Jared that I occasionally thought about switching career tracks to become an experience designer.

Less than two years later, I stood in one of the first Adventure Series rooms at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, standing in the middle of a design I’d only ever seen on a projector screen, the same room you can see in the screenshot above, as my daughter’s head was scanned to see if the experimental medicine we’d been giving her had slowed her tumors.

Six months after that, I was talking about it on stage in Orlando, as an example of how designing for crisis can have spectacularly positive results. The video we released last week came a year later, and is a much better version of that first talk. I’m very happy that we can now share it with the world.

As I’ve said before, I came to realize that “Designing for Crisis” was just one piece of a larger puzzle. To start exploring and understanding the whole puzzle, I recently finished co-authoring Design for Real Life with Sara Wachter-Boettcher, to be published by A Book Apart, possibly as soon as March (but there’s not an official date yet, so that could change). In it, Sara and I explore a small set of principles to use in approaching design work, and talk about how to incorporate those principles into your existing design practice. The book is the foundation for a new talk I’ll be presenting at every An Event Apart in 2016 — including this year’s Special Edition show in Orlando.

As soon as the book is available for order, we’ll let everyone know — but for now, I hope you’ll find last year’s talk useful and enlightening. Several people have told me it changed the way they approach their work, and it serves as a pretty good introduction to the ideas and themes I’ve built on it for the book and this year’s talk, so I hope it will be an hour well spent.

CSS:TDG Update

Published 10 years, 4 months pastIt’s time for a semi-periodic update on CSS: The Definitive Guide, 4th Edition! The basic news is that things are proceeding, albeit slowly. Eight chapters are even now available as ebooks or, in most cases, print-on-demand titles. Behold:

- CSS and Documents, which covers the raw basics of how CSS is associated with HTML, including some of the more obscure ways of strapping external styles to the document as well as media query syntax. It’s free to download in any of the various formats O’Reilly offers.

- Selectors, Specificity, and the Cascade, which combines two chapters to cover all of the various Level 3 selector patterns as well as the inner details of how specificity, inheritance, and cascade.

- Values, Units and Colors, which covers all the various ways you can label numbers as well as use strings. It also takes advantage of the new cheapness of color printing to use a bunch of nice color-value figures that aren’t forced to be all in grayscale.

- CSS Fonts, which dives into the gory details of

@font-faceand how it can deeply affect the use offont-related properties, both those we use widely as well as many that are quickly gaining browser support. - CSS Text, which covers all the text styles that aren’t concerned with setting the font face — stuff like indenting, decoration, drop shadows, white-space handling, and so on.

- Basic Visual Formatting in CSS, which covers how block, inline, inline-block, and other boxes are constructed, including the surprisingly-complicated topic of how lines of text are constructed. Very fundamental stuff, but of course fundamentals are called that for a reason.

- Transforms in CSS, which is currently FREE in ebook format, covers the

transformproperty and its closely related properties. 2D, 3D, it’s all here. - Colors, Backgrounds, and Gradients, which covers those three topics in FULL GLORIOUS COLOR, fittingly enough. Curious about the new background sizing options? Ever wondered exactly how linear and radial gradients are constructed? This book will tell you all that, and more.

Here’s what I have planned to write next:

- Padding, Borders, Outlines, and Margins — including the surprisingly tricky

border-image - Positioning – basically an update, with new and unexpected twists that have been revealed over the years (case in point)

- Grid Layout – though this is coming faster than many of us realize, I may put this one off for a little bit while we see how browser implementations go, and find out what changes happen as a result

My co-author, Estelle, has these three chapters/short books currently in process:

- Transitions

- Animations

- Flexbox

Beyond those 14 chapters, we have eight more on the roster, covering topics like floating, multicolumn layout, shapes, and more. CSS is big now, y’all.

So that’s where we are right now. Our hope is to have the whole thing written by the middle of 2016, at which point some interesting questions will have to be answered. While most of the book is fine in grayscale, there are some chapters (like Colors, Backgrounds, and Gradients) that really beenfit from being in color. Printing a 22-chapter book in color would make it punishingly expensive, even with today’s drastically lower cost of color printing. So what to do?

Not to mention, printing a 22-chapter book is its own level of difficulty. Even if we assume an average of 40 pages a chapter — an unreasonabnly low figure, but let’s go with it — that’s still a nine hundred page book, once you add front and back matter. The binding requirements alone gets us into the realm of punishingly expensive, even without color.

Of course, ebook readers don’t have to care about any of that, but some people (like me) really do prefer paper. So there will be some interesting discussions. Print in two volumes? Sell the individual chapter books in a giant boxed set, Chronicles of Narnia style? We’ll see!